George Bellows said, "I don’t know anything about boxing, I am just painting two men trying to kill each other." What underlies the attraction to such violence? As a reenactment of Freud’s postlapsarian, atavistic death instinct outlined in Civilization and its Discontents, boxing flies in the face of the great human tragedy wherein we exchange the destructive impulses of the id for the safety—and neuroses—of civilization, providing a vicarious forum for these unconscious urges to play out. A less pessimistic reading is of the sport as theater in its purest form, stripped of all artifice.

The Boston Public Library’s Rare Books and Prints Department is home to the entire catalog of George Bellows’ lithographs, produced between 1916 and the year of his death in 1925 at the age of forty-two. Of these 193 prints, sixteen depict boxing, bearing witness to an age when the sport, as one reporter wrote, "dominated everything."1 In the first half of the twentieth century, fights carried enormous political weight in regards to national identity and made daily headlines, with salaries of successful fighters dwarfing those of other celebrities. Important bouts at once fomented racial tensions and advanced integration, paving the way for the civil rights movement to follow decades later. Not even someone who claimed not to "know anything about boxing" could feign ignorance of important fights and fighters during this golden age.

Bellows arrived in New York in 1908. Studying under Robert Henri, the founder of the Ashcan School of urban realists, he set out to portray the vice and squalor—largely ignored by the art viewing public—of the metropolis at the dawn of the Industrial Age. More than any other member of the group, Bellows focused on social issues including poverty, war, capital punishment, and lynchings. With its legality under fire in New York during the late teens, boxing, the dark shadow of the YMCA’s virtuous promotion of a healthy masculine ideal, was also a social issue. With thousands of immigrants and natives alike clamoring to compete for the paltry purses derived from fighting, it was, as David Remnick writes, "a game for the poor…who risk their health for the infinitesimally small chances of riches and glory."2

In Europe, lithography was popular among artists since its invention in 1796, but was considered a strictly industrial endeavor in the United States during the early twentieth century. Bellows wrote of his wish "to rehabilitate the medium from the stigma of commercialism," and elevate it to a fine art form in its own right.3 For those unfamiliar with the process, a limestone plate is drawn upon with greasy pencil, charcoal or ink-like media to create a range of marks and tones. Based on the principle that oil and water don’t mix, the stone remains damp during the inking process so the greasy drawing material rejects the water but retains the ink prior to printing. Like his European precedents and contemporaries, Bellows considered lithography a means to recreate his drawings in surprising new ways. His prints soon piqued the interest of American print collectors previously interested exclusively in etchings.

Bellows’ apartment on Broadway was situated across the street from Sharkey’s Athletic Club where, as in other "Prizefighting Clubs" throughout the city, bouts were held in dank basements populated by petty criminals, gamblers, and gangsters. Before long, Bellows could also be counted among the attendees (partly out a desire to experience the dissipation of the city, partly out of his great admiration for Eakins’ boxing paintings). Unbound to the sport’s proscribed rules, fights in these clubs could last for hours, sometimes resulting in deaths. Bellows claimed that he was "not interested in the morality of prize fighting" and that "the atmosphere around the fighters [was]… more immoral than the fighters themselves." Unlike the anonymous, distant crowds of Goya’s bullfighting lithographs4, Bellows situates us ringside where we ourselves become the spectators. In Counted Out (1921), we are horrified to be counted among the leering, bloodthirsty crowd, instead empathizing with the felled fighter, his vitality ebbing like the Hellenistic Dying Gaul.5 Attraction and revulsion never reconcile, but uncomfortably coexist.

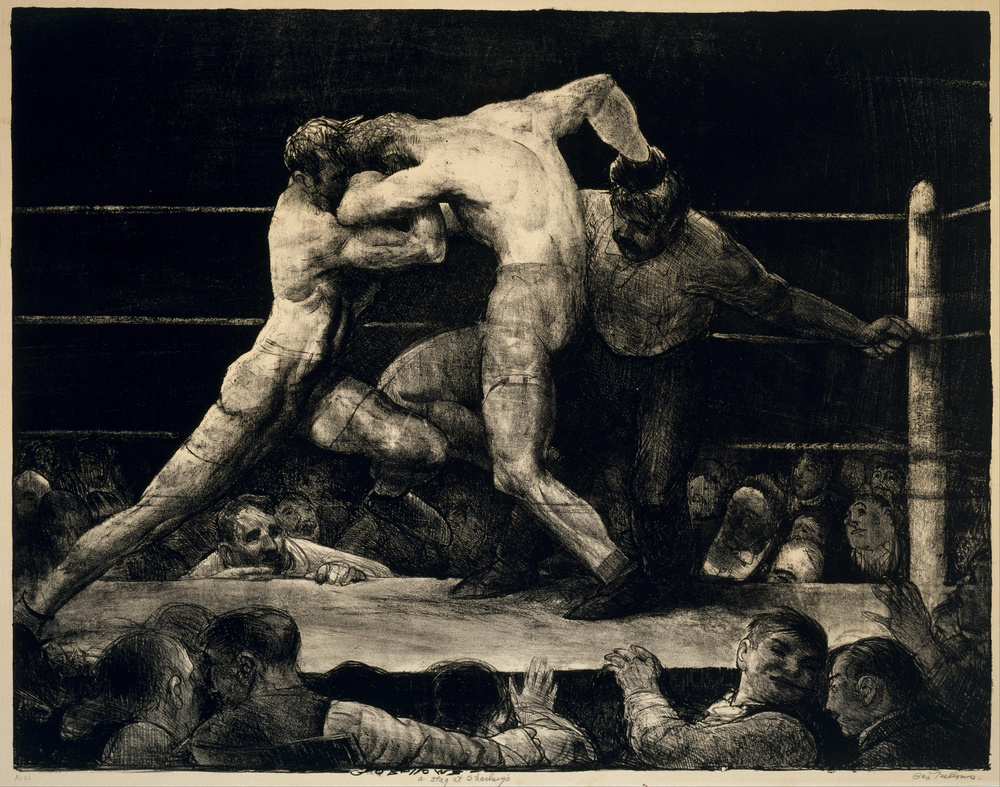

George Bellows, A Stag at Sharkey's. 1917 Lithograph 65.4 x 51.4 cm (sheet) The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

In a suspended moment of histrionic fantasy, the two fighters in A Stag at Sharkey’s (1917) rush, swing and defend, creating a single mechanized juggernaut within a High Renaissance composition. Each boxer lifts a leg absurdly high off the canvas as the other leg extends back to an impossible length. The two heads meet in the center while the cowing referee’s arm describes a line extending upward to end at one boxer’s elbow, forming a triangle’s apex, then drops back down along the shoulder, head, and his opponent’s outstretched leg. The dark basement contrasts with the illuminated pugs and spectators, while silvery tones define muscle that, according to Bellows, constituted his primary interest in the subject (prompting the dubious quote regarding his lack of interest in the sport). The omission of ropes on the viewer’s side of the ring places us squarely within the "amoral atmosphere." Despite our complicity in its violence, Stag remains one of America’s most recognizable and coveted prints.

With its full-fledged legalization in New York, the "noble art of self defense" moved to large, glamorous venues, and Bellows’ boxing prints and paintings soon achieved culturally highbrow status. Boxing had become a passion of the working class and intellectual alike, underscoring Bellows’ rejection of the artist as an "effete academic."6 There is no timeline or chronological charting of the sport’s rise or legal bumps within the prints—he drew stones of legal prizefights and illicit bouts intermittently, some to which he traveled out of state to record either for newspapers or his own edification. We must rely on telling depictions of crowds and surroundings to confirm the location and legality of the fight.

As ticket prices soared, purses grew to astronomical sums. As crowds spanned all ethnic and socioeconomic divisions, gates exceeded all expectations. Bellow’s interest in and knowledge of boxing only grew as he received commissions to portray famous fighters. Sometimes focus was places upon the crowds, the fight almost an afterthought. Preliminaries to the Bout (1916) commemorates the first title fight to allow women to attend, with men in top hats and society women in furs occupying the foreground, relegating the bout to a distant blur.

In late 1919, Bellow’s printer began grinding the lithographic stones to a smoother finish, allowing for more detail and tonal range. It was in these delicate tones that Bellows composed his second most popular print. Dempsey Through the Ropes (1923) immortalizes the greatest sports upset to date, wherein the seemingly unstoppable Jack Dempsey (whose salary tripled that of Babe Ruth during their roughly concomitant careers) was knocked out of the ring during a fight with the challenger Luis Firpo. While the mayhem that ensued in front of a crowd of 80,000 ended in a knockout by Dempsey, the spectacle made for world headlines.

George Bellows Preliminaries to the Bout, 1916 Lithograph 15 3/4 × 19 5/8 in; 40 × 49.8 cm Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.A

Bellows wangled a front row seat to the fight (portraying himself in the lower left corner of the print) as a member of the press for an unpublished newspaper illustration. The fight remains controversial in that journalists in the front row illegally pushed Dempsey back into the ring. In what is certainly a bit of fiction, Bellows said of the incident, "Dempsey… fell in my lap. I cursed him a bit and placed him carefully back into the ring."7 Photographs and newsreels show that Bellows was not among the crushed reporters, all of whom had typewriters. Joyce Carol Oates writes that the print "is a work of imagination, not journalism,"8 and Bellows’ daughter Emma confirms that her father worked from memory, frequently drawing directly on the stone. Indeed, there are many aspects of the print that call into question the accuracy of the scene, particularly the referee shown in mid-count a split second after the punch, his arm again used as a device in creating a triangular composition). Even the wildly famous Dempsey lacks distinguishing features (though Bellows did show care in achieving likenesses in other commissions). Of his sixteen boxing prints, only six of the fighters are identifiable. The rest are likely anonymous figures based on Bellows’ anatomical studies. While he always portrayed the same referees, none are recognizable. But anonymous, real, or imagined, his fighters retain humanity in their predicaments, frozen for eternity within a single, devastating moment.

While we may understand Bellows’ attraction to boxing, we continue grapple with the imagery’s lasting appeal. Impartial to race and status, the prints exhibit an admixture of social classes at a time when the masses were desperate for a quick ticket out of poverty. But as the New Yorker’s John Lardner wrote, "the longer you stay in it, the less you have."9 Bellows captured not just the brutality of two humans in combat, but the desperation and defeat of a sport at its most glamorous and most abhorrent. One explanation for their endurance lies in the viewer’s identification with these most basic of human emotions, whether acknowledged or repressed.

[1] Margolick, David, Beyond Glory: Joe Luis vs. Max Schmeling and a World on the Brink (New York: Alferd A. Knopf, 2005), 344

[2] Quoted in Century, Douglass, Barney Ross (New York: Schocken Books, 2006), 20

[3] Chotner, Deborah, et al., Bellows: The Boxing Pictures (The National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 1982), 67

[4] Brown, Johnathan and Susan Grace Galazzi, Goya’s Last Works (New York: The Frick Collection, 2006), 161

[5] Galata Morente, or "The Dying Gaul," Roman marble copy of a lost Hellenistic Sculpture thought to have been executed in bronze, 230 - 220 BC

[6] Childs Gallery, George Bellows: Master Draftsman and Lithographer, e-catalog

[7] Morgan, Charles H., George Bellows: Painter of America (New York, Reynal and Company, 1965), 263

[8] Oates, joyce Carol, George Bellows: American Artist (Hopewell, New Jersey, The Ecco Press, 1995), 59

[9] Quoted in Guzzardi, Joe, "A Fresh Look at Joe Louis", Lodi News Sentinel, Feb. 21, 2008: 24