As an artist, curators have always mystified me a bit. I once had a curator tell me that he preferred to work with "dead artists, because they put up less of a fuss". I was instantly offended but ultimately, begrudgingly, I could understand what he was getting at. Artists have a solemn duty to advocate for their work, and ego is a vital ingredient in the pie of success. I probably won’t be the last to admit, at times artists can be downright "enfant terribles."

Therefore, it must take a certain kind of tolerance and resolve to work with artists on a daily basis realizing their visions. In that regard, I think MASS MoCA curator, Denise Markonish is actually a bit of a masochist, if not a saint. In the ten years I’ve known her, I’ve seen Markonish tirelessly champion artists and their art. I recently sat down with Ms. Markonish to hash out the shape of the art world and discuss her role as a curator at MASS MoCA. What I found was that for Markonish, being a curator is something deeply personal, and that she’s not afraid to thumb her nose at the art establishment, to take risks or to fail. Moreover, she strongly believes that artists belong at the very top of the art world hierarchy, which she affectionately describes as a "multi-headed-rhizome-beast."

•••

Samuel Rowlett: So, how do you find new art and artists?

Denise Markonish: Through other artists. For me that's one of the biggest stamps of approval. If I see artists that have already shown in a bunch of galleries and museums, personally it tends to make me shy away from them. I'm always interested in finding a mix of emerging artists, and artists who don't necessarily get their due as much. So for me it's really interesting to hear from other artists who they know and what they're looking at. Of course it doesn't mean that I don't go to museums and galleries, of course I look at all that too, and I'm aware of what prevailing trends are. But I'm more apt to take a quick left turn from what those trends are.

SR: Do you think it is the curator’s "duty" to discover new artists?

DM: I do. However, I think "discover" may be a little too egotistical, but I think I would be bored if I was only showing work from artists who had already been vetted. To me, one of the most exciting things is going to an artist's studio for the first time. I've even shown artists who are still in school before. There's no reason not to. If what they're doing is engaging and I want to show it, I'm going to show it.

I like that about MASS MoCA, it is a big place, we get to do ambitious projects, and we’re working on this international level. We could just go for the big names. But if you look at the galleries right now we have the Xu Bing installation, by an amazing, international, well-known artist. And then we have Oh, Canada, that has many unknown artists, and some of whom are even unknown in Canada and are getting a lot of attention now. I feel really happy about that; it feels right.

This also leads to audiences discovering new artists. Maybe someone comes here, and they've not heard of an artist from Canada, or one of the artists in Invisible Cities, they might come for Xu Bing, and yet they get introduced to all these other artists and their work. In a way curating is a kind of education, introducing people to things they otherwise would not have come across.

SR: Would you say you root for the underdog artist?

DM: It's almost like I look for the "sleepers" a little bit. And that doesn't mean that they're not as ambitious, but there are some artists, they may have been working away on this "thing" in their studio that maybe they haven't shown to anybody, well I want to show that!

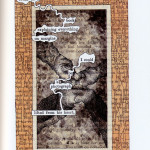

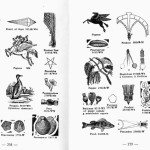

A good case in point is one of the next shows I’m working on called Life's Work. It's a two-person show with Johnny Carrera and Tom Phillips. Johnny used to be based in Waltham, MA, but now lives in Maryland. I got to know him when I was working at the Fuller Museum of Art in Brockton, MA. Ever since I met him he was working on this project called Pictorial Webster's Dictionary, in which he was taking original engravings from the first illustrated Dictionary, creating whole a new pictorial compendium and adding in his own engravings. This is a project he's been working on since 1996. And I was telling someone about this and they said, "Hey, have you ever heard of Tom Phillips?" And I said no. You know, you've heard of Richard Hamilton and R. B. Kitaj, and that generation of artists in Britain, but you haven't heard of this guy. Since 1966 he's been working on this project called A Humument, where he also took an existing text, a Victorian novel, and he's gone through it page by page and make new paintings over the pages, leaving selected text.

What I think is interesting is that these aren't artists that a lot of people know, but yet they're doing a similar thing, exactly 30 years apart. And they both see their work as creating new texts that you can read. In Tom Phillips' work there's actually text, and in Johnny's the placement of images next to each other can be a tool for creativity and creating your own narratives. That's what's really exciting to me about showing these two side-by-side. I think Johnny knew a little bit of Tom's work, but otherwise they weren't aware of each other. That, to me, is really exciting.

SR: It's interesting when you think about the geography or architecture of a dictionary or text, and then you think about the geography of the art world. You know, "how do we all fit together"?

DM: You know it's interesting it was actually Michael Oatman who told me about Tom Phillips. And in Michael's airstream trailer turned spaceship, all utopias fell, there's a stack of books imaged in a stained glass window—books that influenced him—and one of them is A Humument, Tom Phillips' book! It all ties together.

SR: Okay then, thinking about the shape of the art world, if you could liken the art world to any natural or man-made structure, what would it most resemble?

DM: I think it's kind of like a rhizome structure. You know, rhizomes, which are underground but have all these different nodes that stretch out, but they're all connected, and yet it's amorphous, and it can grow into different shapes. I like the idea that a rhizome can re-root itself and grow up somewhere else, but it's all still one system.

SR: So it's an organic shape?

DM: I think it is organic, yeah.

SR: Which may relate to manner in which you're finding artists?

DM: I think if you approach the art world as a very structural thing, a hierarchical thing, to me that gets depressing. Of course there's still a weird sort of Caste system, or hierarchy in the art world. I was talking with some folks the other weekend about this, and they were saying, "Who's at the top? Is it the head trustee at MOMA or the Met, and it trickles down from there?" And one of the people I was with is an artist, and they said, "Well you know the artists are always at the bottom." But if I think of it that way I would get really dismayed at being in this world. So, for me, the artist is always at the top.

SR: That's a refreshing perspective!

DM: I think it's hard for artists to feel they belong there, because the system, as I think it often dysfunctionally works, does not set that up. But, if it weren't for the artists, that trustee, who people proclaim is at the top, wouldn't be in the picture! How can we place the people who are making it all happen at the bottom?

SR: God, that sounds like a sort of Vincent Van Gogh syndrome, you know, that guy died in poverty…

DM: And only then becomes famous? No, that's not okay! Let us all die in poverty! Solidarity!

SR: Amen! I guess the system relies on the makers of culture, making substance or meaning? Why do we still ask, "What is art?"

DM: It's a question that gets asked a lot, but nobody asks, "What is literature?" Nobody says, "What is music?" They're all different heads of the same giant beast, but people feel it's okay to ask, "But how is that art and this isn't?" I think all of this, putting the artists at the top, and not asking "what is art", as a way of retraining ourselves as to how we think about art and how it functions, how this multi-headed beast exists, this multi-headed rhizome beast exists.

SR: A Hydra.

DM: A Hyd-rhizome!

SR: It seems like, if we think about the questioning of art, maybe art is there to question its own existence? It is there for us to ask those questions.

DM: We should always be questioning what we do, but we shouldn't pick just one thing to question. And to pick that one big question "What is art?", It doesn't really serve a purpose. But, to ask the smaller questions like, "How does this effect me?" even something like, "What is beautiful?" What does that mean now? Beauty kind of has become a dirty word, why? It's more like a micro-scale of questioning, as opposed to "What is God?"

SR: MASS MoCA is not a collecting institution, right? So does that give you freedom or does it restrict you in some way?

DM: Oh, it totally gives me freedom. I think collecting is tricky, because in a way it immediately dates you as an institution, and forces you to give value in a different way to something. Here at MASS MoCA, we can take risks, whereas I feel like with a collection it is harder to take those risks. Because you are like, "Oh, what if in 10 years from now this work is not valid?" If we show an artist, and I ask an artist to make a new work and it's a total failure, which happens, and not because the artist isn't good or I'm not good at my job, it just happens. 10 years from now, I’ll be like, okay, I'm really glad I gave that artist the opportunity, whether the piece was a success or failure, it was an opportunity. The difference between a collecting institution and a presenting institution is that idea of opportunity. Being able to say to somebody "here's your space: do what you want with it".

SR: I'm going to get hard-hitting here. So, failure? That's interesting, could you say you've had some misses?

DM: Absolutely.

SR: Could you name some?

DM: No! But I think there are misses that the artist would agree on, and you know not everything can be successful. To go into a show thinking this is going to miss or fail is not worth it: you just have to go for it. Like jumping into the ocean in Maine before August, you know it's going to be really cold but you do it anyway! If you don't take those risks, then what are you doing this for?

But, those failures are going to happen. Do I have moments where I think, "Oh shit, that sucks. I really thought it was going to be more"? Of course, but if it helped me learn something or the artist learned something, about the process, making it totally worth it. And remember, the general public's memory is short.

SR: Yes, we have a short attention span, especially for art.

DM: We walk into the next room, and...

SR: We're like, "Wait, what is art again?"

DM: Ha!

SR: So, can you go on record and tell me your favorite shows you’ve organized?

DM: No, I can't go on record naming my favorite shows. That's like naming your favorite children! I'm definitely proud of…

SR: Wait, do you think of your shows as your children?

DM: Ha, ha! A little bit, it's definitely really personal for me. It's a job but it's my life. It's something I live and breathe. This is the thing, it's in my brain always. It's funny, today I texted a colleague, Sean Foley, with whom I'm working on a project about the idea of "wonder". "The quote of the day is: Stuff your eyes with wonder, live as if you'd drop dead in 10 seconds, see the world, it's more fantastic than any dream made or paid for in factories". It’s a quote from Fahrenheit 451.

SR: Ray Bradbury.

DM: Sean wrote me back and said, "This is really weird, I wrote this quote down this weekend about how Ray Bradbury wrote Fahrenheit 451 for $9.80. His secret? 'You remain invested in your inner child by exploding every day, you don't worry about the future, you don't worry about the past, you just explode.'" I mean, that's it right there!

SR: Wow, there's that rhizome at work!

DM: Yeah. And so that sums it up right there, it's a passion. No one would get into this field, especially working in small non-profits, busting your ass, and being underpaid if they didn't love it. So, yeah, because of that, I do think of my shows as my children.

SR: So that maybe ties back into the role of the curator, it IS personal, right? It's about personal interests and tastes.

DM: It's what I've always said about Oh, Canada, if someone else had curated it, it would've been a very different show. I wasn't setting out say "This IS Canadian art", or to put together a show that everyone would like, this is my personal experience. So often when you're putting forward theoretical ideas, they're still coming from a personal place. You have to remind yourself of that, and keep connected to it, because that's why you do it.

Here at MASS MoCA, every time I've done bigger projects, rather than a smaller group show, I work on them for years. When I do a project in the big gallery, Building 5, I will work with an artist for 2 to 3 years. So you get to develop these connections. I remember working with Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle, and him saying, "It's our project, not just mine". And, it's really nice to have that affirmed, even though I would never say that "this is mine", but I've had a stake in it. Or something like Oh, Canada which I worked on for 5 years.

SR: I'm going to hypothesize here, but maybe the best shows, the ones that are most successful are the ones where there is a connection or relationship that is built between curator and artist?

DM: Absolutely, especially with our big commissions here at MASS MoCA, you get in with an artist in the very beginning, you’re there when they look at the space for the first time, and they call you along the way and ask you "Well, what you think about this or that"? That reciprocity is really important. I think with the Canada show, you can see how much research went into it, but maybe with a single artist project it may be harder to understand the curator's role for most people. But being that constant sounding board, it’s a more invisible role, but helps to get the project where it is.

SR: So, could you say you lean more towards organizing group shows or solo shows?

DM: I used to always say that I liked group shows better. I liked coming up with an idea, and making this interconnected thing. A solo show to me, seemed less of a challenge. But, that was before I came to MASS MoCA! Solo shows are a real challenge here. From the big space, which is like commissioning for a football field. When we do a solo show they are SO epic. But, you know, I really like the balance of both smaller and larger projects.

SR: Speaking of large, now that you've scratched "Massive Contemporary Canadian Art Exhibition" off your bucket list, what's next?

DM: How did you know that was on my bucket list?

SR: I'm hoping it's not the last item on that list!

DM: Definitely not! So, I'm actually opening three shows at once on April 6, because after Canada I said that I wanted to slow down. Ha! They are Life's Work: Tom Phillips and Johnny Carrera; Mark Dion's Octagon Room, which looks like a bunker on the outside but inside is like a mini retrospective of his work; and the third show is a 10 year retrospective of The One Minute Film Festival. Artists Jason Simon and Moyra Davey started a one minute film festival in their barn in upstate New York. They would invite friends and their friends would invite friends, and everyone would come with a one minute movie. So it was both this act of spontaneous creativity and it was also this interesting social gathering (when they first started YouTube didn't exist). We're showing over 600, one minute movies that encompass that 10 years. The final, 10th year, is an exquisite corpse film, where they invited all past filmmakers each to do a one minute film, each person got the last second of the previous film to play off of.

It's really interesting because Moyra Davey and Jason Simon introduced me to Mark Dion, who I have worked with a number of times. Moyra was in my thesis show when I got my masters at Bard's Center for Curatorial Studies, so I have known her for a long time (and, as an aside, she is also Canadian.) And I've known Johnny Carrera for a while. Michael Oatman, whom I've worked with several times, not only has films in "The One Minute Film Festival" show but he introduced me to Tom Phillips. So I'm really happy to be working on these shows at the same time, because I've been watching these artists for a really long time. In some cases over a decade! So, we will have a big opening for all those shows on the same day as we have the closing for Oh, Canada.

SR: Wow, April 6, party at MASS MoCA!

DM: Oh yeah!

SR: Thinking about MASS MoCA, Massachusetts, and New England. You've been based in New England, you were born in Massachusetts...

DM: It's home.

SR: So what does that mean for you, because a lot of young artists and curators think New York, New York or maybe Los Angeles are the places to be...

DM: Pshaw! No seriously, I've always thought it is interesting that I've done well in the art world by never having gone to a big metropolitan center, where it would've taken me so much longer to build the kind of resume I've built and to be able to curate the shows I've been able to. You know, I got out of Grad school and I was the curator at an art museum, if I'd gone to New York I would've been the curator of somebody's coffee!

I always tell people if you want to move to New York then move to New York but don't feel that you HAVE to do it. There's so much you can accomplish outside of the perceived art centers. That's one of the main reasons why I organized Oh, Canada. I'm a bit of a contrarian like that. And you know New England is home, and there are some really great artists here. However, that doesn't mean I'm pigeonholed to showing just New England artists, I'm also bringing artists from all over the world to New England. I can be an advocate for here, while still having a broad view.

SR: As an artist myself I feel the same way about New England.

DM: There's a real camaraderie here, it's not easy to be an artist anywhere, it takes a lot of work, people are often working multiple jobs. Maybe it's a little easier to be an artist in Canada where they have government funding for artists. But like I was saying in my case, you do it because it's your passion, because you can't imagine, or even know how to do anything else! When I got out of grad school people thought I was crazy, but I just knew going to New York and being part of the scene there and not being able to practice what I wanted to do immediately was going to drive me crazy. I guess I was just impatient!

SR: Do you have any advice for artists?

DM: Make work, regardless of whether you have a show or not. I think too many artists get into the pattern of making work for a deadline, but if you build a constant practice you are bound to be happier and make better work, and just be in that head space more. I think blind submissions don't really work, we get tons of submissions here, and it's not that we don't want to look at them, but frankly there's only 24 hours in the day, and I really don't want to work 24 hours in a day, it ends up more like 12!

I think it's really important to make it personal, don't just blindly submit your work everywhere. Find someone who can make a connection for you, like I said before some of the best suggestions I get are from other artists. Send an invitation, but don't send me tons of stuff. It's just that, well, you see what my desk looks like! I wish I had the time, because I like to see what's out there.

The other thing is you can't get frustrated if you don't hear back right away because it takes time, and that's why it's really important to just keep making stuff. Because, if you just sit around waiting to hear back you're going to get dismayed. It's hard, sometimes artists don't want to apply for juried shows or open calls, I tell them to do it. Look at who the curator is. A number of times I've juried an open call exhibition and found artists that I have later shown. So if you look at who the curator is, and you're not interested in them seeing your work, maybe you don't want to do it. But keep abreast of all those things, because that's another way to get seen. The number of times I've juried, and found artists who've gone on to do projects here, has been a lot.

SR: The whole idea of just keeping working seems really important.

DM: And it can be one of the hardest things, and it might feel like you're working in a vacuum, but people don't work in a vacuum forever. Even in his time Van Gogh had people take an interest in his paintings, especially other artists. And that's the key, building camaraderie with other artists, and being open to all kinds of feedback. Community is important.

SR: Any other advice for young curators?

DM: (whispers) Don't do it!

SR: "Abandon all hope, ye who enter here"?

DM: No, but seriously, don't do it unless you can't imagine ever doing anything else. Because, it will be your life, it's a lot of work. Approach it openly; keep your eyes open all the time. Like Ray Bradbury said, "Stuff your eyes with wonder".

Most importantly, follow your gut; don't do what you're supposed to do, do what you want to do.

- Bill Burns’s work from Oh, Canada

- Moyra Davey, One Minute Film Fest

- Denise Markonish’s Office

- Tom Phillips, 5th Edition Humument

- Johnny Carrera, Peen to Perception, in Pictorial Websters

- Janice Wright Cheney’s work in Oh, Canada

- Mark Dion, The Octagon Room