John Ruskin was born February 8, 1819, in London, a few months before Queen Victoria’s birth. His parents, John James and Margaret Ruskin, were first cousins, his father a Scottish wine merchant, his mother a particularly devout Protestant. They had married in 1818 after a long courtship, extended by John James Ruskin’s father’s debts, which ultimately led to his suicide in 1817. John James (later described by his son as "a violent Tory of the old school") dutifully repaid everything his father owed and ultimately prospered as a wine merchant, but the grandfather’s errors and insanity haunted young John’s childhood. "It was partly as a result of this catastrophe that John James Ruskin came to place an unusually high value on the security of an orderly family home, a sentiment that his son shared to the full," writes Dinah Birch in her introduction to John Ruskin: Selected Writings, published by Oxford World’s Classics in 2004. "There is no doubt that [Ruskin] was the centre of his anxiously nurturing parents’ concern, and the focus of their family ambitions." Ruskin was schooled at home under his mother’s tutelage, which included especially rigorous study of the King James Bible. "My mother’s general principles of first treatment were, to guard me with steady watchfulness from all avoidable pain and danger; and, for the rest, to let me amuse myself as I liked," Ruskin writes in his late work, the autobiographical Praeterita ("Of Past Things," 1885-1889). "No toys were at first allowed . . . I had a bunch of keys to play with, as long as I was capable only of pleasure in what glittered and jingled . . . I soon attained serene and secure methods of life and motion; and could pass my days contentedly in tracing the squares and comparing the colours of my carpet." Ruskin’s eye was thus trained in the skill of sharp observation, his sense of perception honed. Those talents developed into an interest in poetry; young Ruskin published his first poem in 1829, when he was just 10 years old. Effie Gray was born that year.

Ruskin’s parents expected him to become a distinguished Clergyman. However, when he entered Christ Church at Oxford in 1837, as a "gentleman commoner," he was largely accomplished in drawing, painting and poetry, not the subjects required an illustrious career as a man of the Cloth. Ruskin applied himself in his studies at Oxford, but didn’t excel in them. He was exceptional writer, however, and after he graduated in 1842, Ruskin published his first major work, Modern Painters (1843). Modern Painters is nothing if not a sensory text, as Ruskin’s richly describes nature as we see it, versus nature as it might be. Ruskin is ever the prescient boy who studied carpet patterns, rooting his portrayals of circles, angles and shade into what can be witnessed with the naked or untutored eye. "Observe your friend’s face as he is coming up to you," Ruskin writes in Modern Painters. "First it is nothing more than a white spot; now it is a face . . . Now he is nearer still, and you can see that he is like your friend, but you cannot tell whether he is, or not . . . Now you are sure, but even yet there are a thousand things in his face which have their effect in inducing the recognition, but which cannot see so as to know what they are." All elements have a thousand particles to them, Ruskin intends. Each particle may not be visible, but when they are presented at a certain proximity to us, their mass becomes recognizable. In what became his signature style—a melodic, imagistic prose—Ruskin asserts that "nature is never distinct and never vacant, she is always mysterious, but always abundant; you always see something, but you never see all."

It’s tempting to consider what sentiments Ruskin is betraying in sentences such as this when considering his marriage. When he married in 1848, Ruskin was 29 and a successful writer. He was renowned as the first art critic to consider a living, or contemporary, painter. A second volume of the same title followed Modern Painters in 1846, and in it, he praises the "imaginative artist" as one who sees and paints "not only the tree, but the sky behind it; not only that tree or sky, but all the other great features of his picture." The "imaginative artist" is one who sees the natural object and depicts its form, but moreover, its essence, and place within a picture. This "imaginative artist" is a sensitive mind, feeling and understanding all, even that which cannot be viewed by the human eye. This perceptive mind comprehends there is always more than what meets the eye.

Certainly there was an unspoken, unseen bond between Effie Gray and Ruskin: though they had a ten-year age difference between them, they had essentially grown up together. The Grays and the Ruskins were family friends. After his father’s suicide, John James Ruskin moved out of his family home in Scotland for the wine business in England, and the Grays moved in. Effie Gray stayed with the Ruskins when visiting London and the Ruskins often traveled up to Scotland and their ancestral estate on holidays. When John Ruskin and Effie Gray married on April 10, 1848, in Scotland, on that very estate where Ruskin’s grandfather had committed suicide, there was history between them. And still, though their histories would be forever bound, their union was never realized. Ruskin refused to have sex with Effie on their wedding night. Effie later wrote her parents that Ruskin at first said it was because he hated children, or his religion, but that he finally confessed and said that "he had imagined women were quite different to what he saw I was, and that the reason he did not make me his Wife was because he was disgusted with my person the first evening 10th April." It seems that to Ruskin, Gray was more mysterious and abundant than her "person" suggested in the light of day, clothed, and for precise reasons that were forever private to him, he chose not to fully experience the full nature of marriage.

If their familial home nurtured their romance, Venice provoked their separation. Ruskin’s proposal wasn’t Effie’s first, and many accounts suggest that the couple’s temperaments were particularly contrary to each other. A few years after their marriage, the couple traveled to Venice for John to research the city for a book, The Stones of Venice (1851). While John studied and sketched the city’s ruins and quickly deteriorating buildings, Effie exuberantly flirted with many of the Austrian soldiers stationed there. The Stones of Venice is a brooding text. Yet it also sounds a hopeful note in its call to destroy the Renaissance’s legacy and start anew with a more modern art. "It is Venice, and therefore in Venice only, that effectual blows can be struck at this pestilent art of the Renaissance," writes Ruskin at the start of The Stones of Venice, volume one. "Destroy its claims to admiration there, and it can assert them nowhere else." Correspondingly, in the collapse of their marriage John and Effie Ruskin would enable each to start fresh.

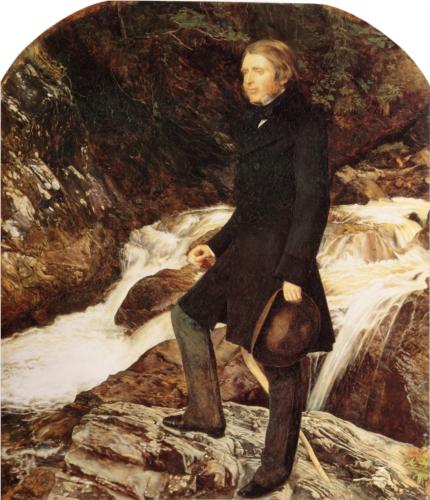

After the Ruskins returned to England from Venice, Ruskin was challenged to a duel by one of Effie’s crushes, and thus resolved to end his marriage. In 1853, as the Ruskins prepared to travel to Scotland on holiday, Ruskin invited John Everett Millais, a Pre-Raphaelite painter whose works Ruskin had admired and defended for a few years. Perhaps Ruskin looked forward to chatting with Millais about his work, and spending time with him away from the London art scene. Perhaps. In the end, his motives were fueled by his desire to escape Effie and his marriage, as he set about to match Effie and Millais romantically, leaving them alone together as much as possible. Soon into their stay, Millais decided to portray Effie in his painting The Order of Release (1853). Sharing long hours posing and painting, respectively, Millais and Gray indeed fell in love, and the latter quickly arranged for her marriage to Ruskin to be annulled on the grounds that it was never consummated. She underwent invasive—one assumes humiliating—procedures in which two different doctors examined her to insure her virginity (required for annulments at the time). By 1854, John and Effie Ruskin were husband and wife no more. Gray promptly proceeded to marry Millais and have eight children with him. As for Ruskin, he eventually met and fell in love with a 10-year-old Irish girl, Rose La Touche. Her parents forbade Ruskin to marry their daughter.

"I have written these sketches of effort and incident in former years for my friends; and for those of the public who have been pleased by my books," Ruskin writes in his preface to Praeterita, and continues, "very certainly any habitual readers of my books will understand them better, for having knowledge as complete as I can give them of the personal character which, without endeavor to conceal, I yet have never taken pains to display, and even, now and then, felt some freakish pleasure in exposing to the chance of misinterpretation." Though his biography and legacy has been interpreted, re-interpreted and indeed misinterpreted for over a century, a new generation of readers will find intrigue in the life and words of Ruskin. This November, Robert Brownell, a noted Ruskin scholar, will publish Marriage of Inconvenience, a narrative of the Ruskins’ marriage and annulment that includes new documents and evidence. Emma Thompson and her husband Greg Wise have been working on a film about the marriage for a few years; Effie appears to be in post-production now. Both are only the latest in a long list of books and films to take Ruskin, Gray and Millais as their subject. They won’t be the last, but we will probably never fully understand the ambiguities between Mr. and Mrs. Ruskin.

- John Everett Millais, John Ruskin, (1853)

- JMW Turner, Shade and Darkness, The Evening of The Deluge (1843)

- JMW Turner, Norham Castle, Sunrise (1845)

- Thomas Richmond, Euphemia (‘Effie’) Chalmers (née Gray), Lady Millais (1851)

- John Everett Millais, Self Portrait (1853)

- John Everett Millais, The Order of Release(1852)