Excessive enthusiasm for the sensory world can lessen one's critical edge. But last week at Matt Saunders' artist talk, my sliding scale of wonder grew a little narrower. In the presence of such discipline and lucidity, I had to re-calibrate.

Several aspects of Saunders' talk made it memorable. Naturally, the work had something to do with it. Beyond that, his self-awareness and his generosity towards those present was remarkable. "What is this?" he asked of his own recent work, displayed on the screen, and quoting Mary Kelly's approach to critique. He proceeded with the observation, hesitating as though he were seeing it for the first time: "these are photographs that are

- scaled as paintings

- that reveal their process

- that are figurative but mediated

- that have a sense of not being 'from life'

- that seem to use sampled or found images

- that possess the quality of a film-still

- that use non-photographic materials in a photographic way"

It is rare for an artist to present enough remove from their work to see it as a stranger would. It's also a strength. Rather than offer us a strictly chronological take, Saunders began with the present, deconstructed the finished form, and only then took us backwards in an attempt to reveal how he had arrived at it. For all the students and teachers present, it was a gift.

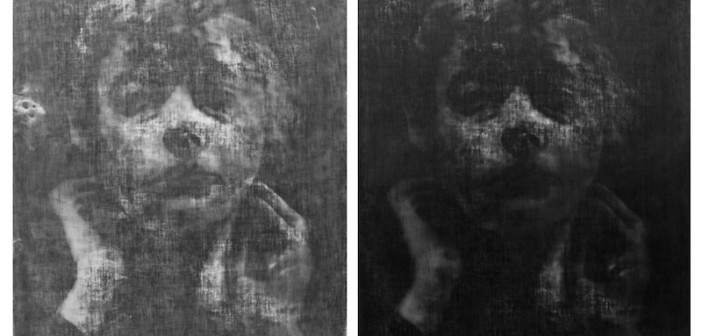

His work, he says candidly, is a "narrative of dissatisfaction." It is lonely and studio-driven and bears resemblance to a laboratory experiment in failing better *. I'd even venture so far as to say that Saunders seeks failure. His attraction to photographic processes, as a painter, has much to do with upsetting a delicate chemical balance and embracing the unpredictability that comes with a lack of mastery. As a painter he is, perhaps, too experienced, too certain of a result, and thirsty for that element of surprise, the error of a medium intruding on his process. Rather than faithfully observe photography's capacity to reproduce, Saunders coaxes these chemical upsets into being by constantly throwing wrenches: visualizing the negative of an image and painting it directly onto a porous canvas of ecclesiastical linen; contact printing it at different distances from the paper in order to throw the image out of focus; thickening the negative with scotch tape, spray paints, oils and other emulsions, applied with wide brush strokes. As he becomes more adept at darkroom chemistry, he deliberately starts to mix incorrectly, causing fixer failure and unstable prints that will change in time.

But why?

Saunders' imagery deals mostly with fallen stars and forgotten icons of the silver screen. His portraits are based on pre-existing images that he has collected from newspapers and old magazines, found in books or on postcards, and archived. There is more than a touch of the obsessive in his approach. Certain faces appear time and again: those of Hertha Thiele, Ugo Kier, Asta Nielsen. As a graduate student, he used to capture the frozen image off the television screen and paint the same frame of the movie repeatedly, modulating color, tone, line, surface, in each copy. He worked this way on scenes from Andy Warhol's Blood for Dracula (1974) and Christoph Schlingensief'sEgomania (1986), both starring Kier in camp dress and make-up.

Matt Saunders, Hanna and Mirror, 2003

Matt Saunders, Hanna and Mirror, 2003Oil on plastic

31 1/16 × 55 inches

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

In these earlier paintings on mylar, Saunders would use the translucent surface to split the image onto both sides: two paintings merged but were also mediated by the material that held them. This doubling up—going beyond the subject and its double, we're presented with the image and its doppelgänger—is manifest in his newest photographic paintings that opt for seriality rather than layering. It's a literal double-take.

To me, it isn't adulation alone that leads Saunders to maniacally reproduce images of former movie icons, but a fascination with the process of creating history through the act of archiving. Given the amount of time he devoted to explaining his studio process rather than prioritizing his research and subject matter, it's fair to say that the work is as much about the nature and physical make-up of an image as it is about the image's content. Our signifier isn't the cinema star alone, but the material which contains the star's image; the signified isn't only celebrity's fickleness but the unreliable, incomplete, imprecise and shifting nature of historical narrative, owing to the presence (or absence), wealth (or scarcity) of documentation.

Through his paintings, Saunders is building and then monumentalizing his own preferred archive. And yet, because of the unstable, moving (animated even, in his video work) nature of the materials chosen to create it, he seems to acknowledge the inevitability of the document's demise. Or perhaps he feels that the life-cycle of an image, like that of a living being, should have its own death inscribed within it. Isn't that what makes us hold each so dear?

* to paraphrase Samuel Beckett

Matt Saunders was speaking at BU within the context of Lesley University / AIB's series Art Talks.

He is currently a Visiting Lecturer on Visual and Environmental Studies at Harvard University.

- Matatt Saunders. Asta Mirror (Double), 2011-2012 Silver gelatin prints on fiber-based paper 2 sheets, each 57.75 x 39.75 in. Courtesy of the artist, Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, Marian Goodman, Paris, and Harris Lieberman Gallery, New York

- Matt Saunders, Hanna and Mirror, 2003 Oil on plastic 31 1/16 × 55 inches Whitney Museum of American Art, New York