I’ve seen von Heyl’s work before, fist at the ICA/Boston in 2012, and again at Petzel Gallery in New York last fall. Her large-scale paintings pair well with the airy proportions of those venues, which seem to invite the works to assert themselves beyond the dimensions of their actual supports.

Charline von Heyl, Bois-Tu De La Bière?, 2012. Acrylic on canvas

Charline von Heyl, Bois-Tu De La Bière?, 2012. Acrylic on canvas82 x 78 inches

Courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York

Seeing von Heyl’s paintings at the Rose, I couldn’t help but think that the subterranean gallery manages a reverse optical trick. The dimly-lit space may be a conservational necessity for Wols’s fragile half-century old watercolor and ink works-on-paper. But the gallery’s low ceilings—relative to von Heyl’s six foot canvases—and the choice of slate-gray wall color have the effect of hemming in the canvases, robbing their innate ability to project out into the room. The paintings seem tamed somehow, as if presented as illustrations than the big, rangy, aggressive works they are.

Witnessing this phenomenon—that is, how paintings "behave" differently in different settings, led me to consider how the relatively small show might look if works were segregated by medium. The arresting Blue Phantom, and the few other of Wols’s oil paintings on view, although easel sized, hold their own against the imposing von Heyl’s in a way unfair to expect of watercolor and ink studies on paper. Oil paintings, especially large-scale oils—and certainly von Heyl’s—have a way of retaining an indexical imprint of the exertion expended in their making. Small watercolor studies have a similar imprint (as the Wols presented here do); and usually suggest carefully considered exertion from about the elbow down,-but not the full body work-out that large paintings suggest. This subtle but palpable difference calls for a kind of mental gear-shifting while walking among the interspersed media.

Charline von Heyl, Carlotta, 2013. Oil, acrylic and charcoal on canvas

Charline von Heyl, Carlotta, 2013. Oil, acrylic and charcoal on canvas82 x 76 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York

At the entrance to the exhibit Siegel placed a striking, graphically-charged grid of works on paper by von Heyl (which notably, are from the same series currently representing the artist at the 2014 Whitney Biennial). What if a grid of Wols’s watercolor and ink works (one that takes into consideration the variety of period frames) were placed on an opposite wall? Would that action allow the assertive oil paintings more breathing room? The segregation might also permit medium-specific lighting. It seems a shame to let conservation measures necessary for only a few works dictate the look and feel of the entire exhibit.

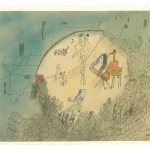

Wols, Le cirque; Prise de vue et projection simultanée(The Circus; Simultaneous View and Projection), ca. 1940.

Wols, Le cirque; Prise de vue et projection simultanée(The Circus; Simultaneous View and Projection), ca. 1940.Ink and watercolor on yellowish paper, on backing (film?)

9.29 x 11.69 in. Courtesy of Karin und Uwe Hollweg Siftung, Bremen

On a subsequent visit to the show, I was better able to take the installation in stride and focus on the works themselves. It was a rewarding experience. On the rear wall is an uncharacteristically spare von Heyl titled, Bois-Tu De La Biere? (2012). It has a traffic-sign yellow ground, on top of which sketchy black lines minimally describe the rectangular dimensions of the canvas---or in an alternate reading consistent with her desire to elude painterly categorization, perhaps is a sketch of a man’s head in profile. Beside is on the wall is a quote from von Heyl, describing the body of work to which the painting belongs. "These new paintings disappointed a lot of my artist colleagues with their flatness. These were not the paintings I wanted to make, but are what I wanted to see. And that’s what wins in the end," reads the quote. In the end we win for having this show offering an arc of von Heyl’s artistic life, from her first influences in the form of Wols’s visionary paintings, to this latest work where she continues to take the kind of painterly risks that confound —and exhilarate.

- Wols, Le cirque; Prise de vue et projection simultanée (The Circus; Simultaneous View and Projection), ca. 1940. Ink and watercolor on yellowish paper, on backing (film?) 9.29 x 11.69 in. Courtesy of Karin und Uwe Hollweg Siftung, Bremen

- Charline von Heyl, Carlotta, 2013. Oil, acrylic and charcoal on canvas 82 x 76 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York

- Charline von Heyl, Bois-Tu De La Bière?, 2012. Acrylic on canvas 82 x 78 inches Courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York