"Toy camera" used to mean just that—a cheap plastic camera produced as a toy and sold or given away for use by children. In the past decade, as film photography overall has been outpaced a gazillion-fold by digital image-making, this distinction has faded like your ancestral Polaroid memories, and the label has come to be used interchangeably with "lo-fi" or low-tech. Any film camera with limited exposure controls (or none at all) is now lumped into the "toy" category, even cameras from the 1930s-1950s that in their time were the equivalent of the Instamatics of the 1960s-'70s, or the point & shoot cameras of today. The call for entries for the first annual Somerville Toy Camera Festival used this broader definition, and even included cell phone cameras (odd, given the level of control available on today's phone cameras, but maybe the organizers feared alienating the masses who use Instagram and Hipstamatic to mimic the toy camera look?). As it turned out, the majority of the images selected for the Festival's three shows were made with bona fide toys; but one point these shows reinforce is that in the right hands, the tool hardly matters.

There's an active film photography community online, and a strong "lo-fi" photography presence within it, with good reason: the most popular toy cameras are medium format. Like Hasselblads and Bronicas, they produce negatives more than twice the size of 35mm film, which allows for greater detail at larger print sizes (why this is still important to so many people at a time when the vast majority of images viewed are viewed on-screen is a topic for a longer post....or maybe a master's thesis). And though prices have risen dramatically in recent years, with a little perseverance it's still possible to find Holgas, original Dianas/Diana clones, and especially the iconic and nearly indestructible Kodak Brownie Hawkeye, for well under $25. Toy cameras are film photography's gateway drug to medium-format shooting: once you realize the image-making power at your fingertips, you're hooked.

And it's not all light-leaks and optic imperfections with these cameras, either—many Brownie Hawkeyes, in particular, had impressively sharp glass lenses, and you might have to try two or three Holgas before you find one with the trademark dark vignetting at the corners or mysterious double-exposed edges. Juror Isa Leshko obviously knows this terrain well: despite toy cameras' reputation for producing images with a certain look, many of the photos she chose for these shows are refreshingly lacking in those high-profile quirks. The absence of clichéd lo-fi subject matter is another delight—thankfully, neither Nave show includes a shot made from the ground, looking up at a spinning amusement park ride (a shot Leshko herself helped popularize, that's since become so ubiquitous among toy camera shooters you'd think every Holga came pre-loaded with one).

So the Festival gets big points for avoiding predictability. The dreamy softness that's a hallmark of plastic lenses is present throughout the show, but aside from that, the major trends in evidence here are things more closely associated with film photography in general than toy cameras in particular. Leshko's selections—including plenty of multiple exposures, pinhole images, in-camera panoramas shot across multiple frames, and at least one flirtation with alternative processes—reflect the fact that today's toy camera enthusiasts (many of them digital natives), aren't just rockin' their goofy-looking plastic cameras as badges of hipster cred, they're using them to explore a broad history of photographic technique at relatively low cost.

The shows remind us, too, that the tools we use to make pictures are only that: tools. More controls can make the photographer's work easier, but they're not necessary to make great pictures. The best images in these shows are simply strong photographs, not reliant in the least on the quirky characteristics of the cameras used to make them. That's not to say all this work would have been made with any camera—Kathy Chapman's moody, gorgeous "Charlestown Bridge," Michelle Sheppard's cemetery studies, and the lush multiple exposures by J.M. Golding and Elizabeth Wood take the thick atmospheric quality the Holga imparts as a natural starting point to build on. And photos by Perry Dillbeck, Suzanne Révy, Warren Harold, Meg Birnbaum, and Sarah Fields stand out on fundamentals—shaping a narrative, connecting subject and viewer, setting a mood, suggesting multiple interpretations—and it's doubtful they'd be stronger if shot with the best equipment money can buy. Or maybe they would, on technical measures, but it's not likely the work would gain anything very substantive as a result. Toy cameras, yes. Amateur photos? Definitely not.

- “Fishing Pole,” Holga image by Suzanne Révy

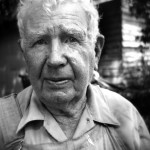

- “Jack Parris” (from the series The Last Harvest), Holga image by Perry Dillbeck

- “Carwash, My Summer with Optimus Prime,” phone camera image by Shawna Gibbs

- “Water Balloons” (from the series Alternating Weekends), Holga image by Warren O. Harold

- “Exhaustion after a firefight” (from the series Battle Company), Holga image by Erin Trieb

The Somerville Toy Camera Festival, organized jointly by the The Nave Gallery and Washington Street Art Center and juried by photographer Isa Leshko, consists of three exhibitions hung in three venues during August and September. The inaugural show, at the Washington St Arts Center, ended August 31; exhibits at the Nave Gallery and Nave Annex run through September 28 and 29, respectively.

Photos courtesy of the Nave Gallery and the artists.