Woodman was a prodigious maker of self-depictions. These images, which were created regularly throughout her career, give the viewer a multifaceted view of the figure she seeks to portray. Created nearly exclusively in black and white, these images are often haunting in the simultaneous likeness and unlikeness they portray of Woodman. Though Woodman is physically present in these works, the images break from the historical tradition of "self-portraiture" in a variety of ways. There is no visual claim that these images are depicting the artist as one may find in earlier prototypes, where artists often portrayed themselves with the tools of their trade. Woodman, however, is said to have used herself as the model for her works mainly due to the convenience of the practice.1 This theory suggests that the content of the works would have been identical had Woodman been able to procure models aside from herself. In this way she projects onto herself, and performs herself, what she would have asked of other people, acting as an orchestrator of movement and performance.

The concept that Woodman was not interested in portraying herself personally in these images is supported by the definition of what an artist is that was instilled in Woodman by her parents. Her mother, Betty, was a ceramist and her father George was a painter. Her parents were focused on their work and in a recent documentary, The Woodmans, directed by Scott Willis; they stressed the seriousness they conveyed to their children about their profession.2 In the same documentary, the couple also points out that they always promoted the idea that artist intention should be removed from the art-making process. This is significant because Woodman would likely have absorbed that idea from a young age. Woodman’s upbringing in a home so dedicated to the concept not only of making things, but also to being this type of artist, is important.

As a child, she often visited museums in Italy, where her family had a home. While in the museums, her parents would give Woodman a sketchbook and allow her free rein of the collections.3 This allowed her to form an understanding of the way women were presented throughout the canon of art history. She began taking photos at the age of 13, commencing with an image of herself. In spite of this self-interest, Woodman’s experiments are unrelated to her own personality as evidenced by the stylistic interpretation considered by many leading scholars. In Bachelors, her important collection of essays, Rosalind Krauss points to Woodman’s works as answers to universal questions of how images are made.4 In this way, Woodman’s images must be understood as a diary of conceptual concerns rather than a collection of self-representations related to her emotional state. This fact is evidenced further upon careful inspection of the visual structure of works throughout her production.

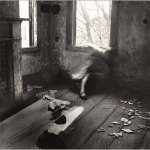

In Woodman’s House series, completed during her undergraduate years at the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence (1975-1979), the artist is seen transforming herself and disappearing into the environment. She is subsumed by the house, encompassed in it, and made a structural element in the space. In House #3 dating to 1976, Woodman is seen in the derelict parlor of a decrepit home in Providence. The plaster walls of the room collapse onto a floor buckled by age and water infiltration. Woodman’s scurrying movement is captured by a long exposure as she slides down the wall just beneath the bright light of a window, which, along with a window at left, provides the only illumination for the space. It is clear here that Woodman is forming a unique visual relationship with the house. This points to a fascinating trope in the larger context of feminist art production.

The theme of the woman in relation to the domestic space of the house is a rich metaphor, particularly when viewed through the lens of second-wave feminism. It was often utilized in feminist works, perhaps most potently in Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro’s Womanhouse of 1972. The renowned scholar Linda Nochlin raises the issue that in most of the canon of art history, women were defined in the visual tradition by their "defining domestic and nurturing function."5 The concept of the woman’s relation to the home is explored in depth in Woodman’s House images in a way that strikes a different tone. Unlike works such as the 1947 image Woman House by French sculptor Louise Bourgeois where the female body appears to be trapped within the cage of the domestic space, Woodman uses the media of photography to portray the woman as a transformative figure who is negotiating her relationship with the domestic space. While Bourgeois’ woman is an inmate, Woodman’s is transitioning into becoming a part of the house. While the figure in Woman House appears to be stuck inside a structure, the figure in Woodman’s imagery exercises the option of disappearing or transforming in relation to it.

The fact that Woodman disappears into the background of a house is significant. Many authors have cited this element of Woodman’s imagery as important to what would, after her death, be particularly associated with the feminist interrogation of woman as domestic captive.6 In the 1970s, at the height of the development of second-wave feminist-theory, this theme becomes increasingly important. Woodman’s interest in the status of a woman within the domestic space at this same time is telling on several fronts: it evidences Woodman’s familiarity with feminist art and theory and it enables the viewer to read the disappearance of the artist as a fact that is unrelated to her later suicide, an event that scholars have tended to read back into her work. Woodman should be understood to be playing out the role of all women in her disappearance into the domestic space, but as distinct from earlier works such as Bourgeois’ in her active struggle against it. This notion of disappearance continues to appear in her other works, including similar projects created while she was a student.

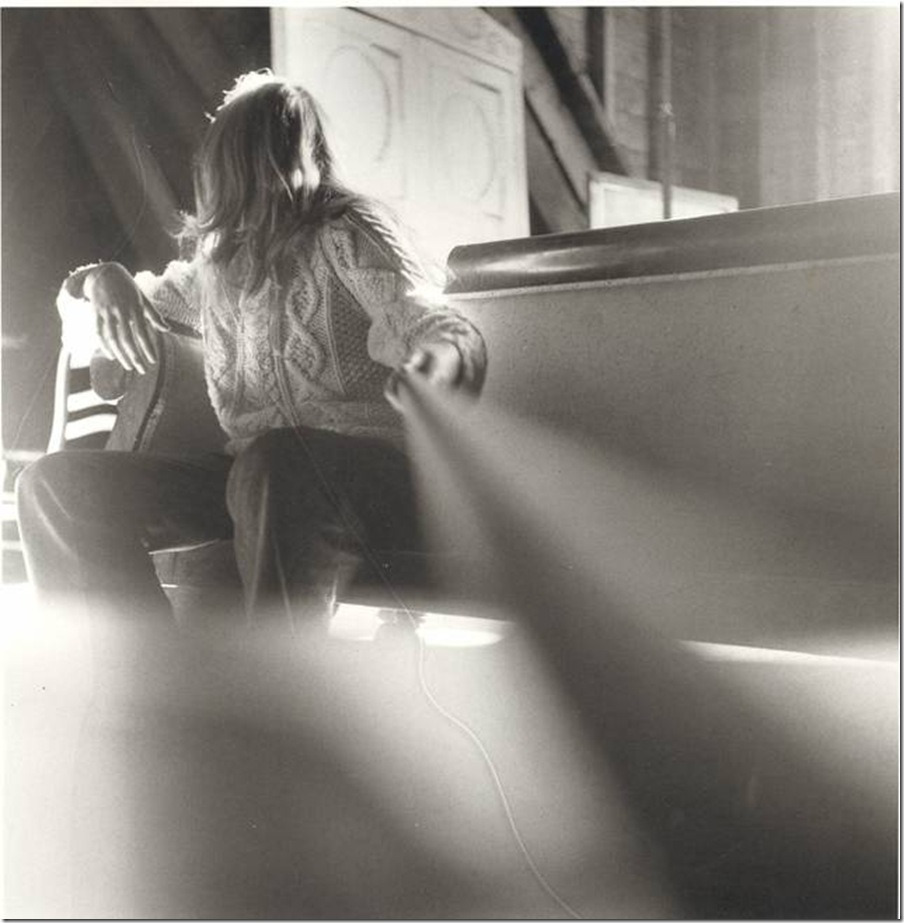

In her Space2 series of 1977, another project from her years at RISD, Woodman is enveloped once more by the fabric of the house. In another, similarly ancient-looking room, Woodman’s body transforms yet again, becoming a chameleon against the decaying wall. Her head is not visible in the picture plane and her upper and lower torso are covered by the remnants of wallpaper that have detached from the wall in front of which she stands. Her stomach and feet are bare and visible, forming an interesting counterpart to her covered torso and legs. The image is striking for several reasons. It shows Woodman still, unlike the images of the artist in motion in the House series. Here, without struggle, Woodman begins to embody the architectural space by applying herself to its surface. While the previous images could be classed as transformations insofar as they display Woodman changing before the eyes of the viewer, this image presents the artist as a static element of the house. The sight of woman becoming object, particularly in regard to the bark like wallpaper that covers her, brings to mind the myth of Daphne, who, fleeing from Apollo, was transformed into a tree to escape his grasp. This may be the first allusion to the story, which Woodman will later reprise in a much more direct way. Here, though, the viewer can see the foundations of this stylistic curiosity, which continued throughout her work. In order to get a better grasp of these stylistic explorations, it is important that the viewer have a broader context of Woodman’s life at this time.

Woodman traveled to Rome with the RISD Honors program in 1977. Stephan Brigidi, a noted American photographer and professor, had recently received his Master of Fine Arts from RISD and, accompanying the RISD undergraduates during his Fulbright year, had sublet Woodman’s apartment. Thus, his opinions and insights into Woodman’s personality are valuable, as he shared the space in which she lived and worked. Specifically, Brigidi outlines the relationship of Francesca to her peers and professors, particularly Aaron Siskind, a well-known photographer and Woodman’s teacher at RISD. Brigidi believes that Siskind did not take Woodman’s work seriously.7 He admits that this may be due, in part, to Siskind’s own personality, but it was apparent Siskind worried that Woodman was flighty and messy. Brigidi believes that, at least at the time he interacted with Woodman in the late 1970s, her work had not yet fully matured. Brigidi also points to the fact that the images presented of Woodman in her own body of work are not images of who she really was: "What we know through her photography is her persona."8 This supports the idea that the images Woodman is creating of herself are not self-portraits. They depict stylistic tropes that she was interested in exploring but cannot be said to tell us anything about her personal struggles.

While in Rome, Woodman created more self-depictions, and reprised the concepts of disappearance and absorption by the physical world. In one image from her Roma series, Woodman presents herself once more against a bare wall. She is the single focal point and lacks specific context. The image solely presents Woodman and the wall, which as in her House images, appears to be in a poor state of repair. This worn textural quality is reminiscent of many of the surfaces her professor Siskind explored in his own work. In this image, she is nude from the waist up and below she is covered by a delicately patterned dress; the skirt of which matches the lower half of the wall in its patterned implications. She does not completely disappear into the wall, but like a chameleon, changes only on the surface. Her skin becomes the skin of the wall in its matching tones. A deep shadow cast to the left of her body reveals that, although she mimics the wall, she is not part of it. Perhaps, again, this is a domestic space. There is an uncertainty about the atmosphere, a removal of content which renders the piece as yet another stylistic exploration, though now she takes on the motif of which Siskind was so fond. In his work of 1948, Chicago, Siskind too explores the deeply textured surface of peeling paint on a wall. Woodman adopts this pattern but inserts the female body into a space that Siskind leaves vacant, depicting a transformative relationship between the woman and space. With the added knowledge of Siskind’s style, the images from her Roma series can be read in two very divergent ways. First, they may be considered as a playful homage to the work of a professor and mentor she admired. They may also, however, be understood as assertive challenges to an authority figure with whom she may have had disagreements. No matter the conclusion though, it is clear that these images are examples of Woodman exploring formal concepts she was interested in and had seen in the work of her professor, and not necessarily depictions of an internal struggle.

In some images, Woodman alludes to biological as well as formal relationships. In one photograph from her time spent in New York prior to her death, Woodman depicts herself against yet another decrepit wall. The surface recedes, revealing a unique herringbone pattern formed by the lathe that once supported the now-absent plaster. This image is particularly rich and striking in both its use of conceptual and visual pairings. Woodman stands at the far left of the picture plane with her back to the viewer; clothed in a cover-up whose tone and texture replicates the character of the wall. In this image, she does not merge with the wall as she has before. She holds up to her bare back the spine of a fish. This layering suggests several ideas. First, it acts as a unique external x-ray of the body. The spine of the fish mimics her own spine and reveals her inner structure in the same way that the flaking plaster reveals the structure of the wall. In this way, she associates herself with the wall and with the fish. She recognizes herself as a biological being, like the fish, and alludes to the sameness of bodily structures. She then goes further and alludes to the association of humans with the built environment. Like humans, structures have skeletons, and also like humans, buildings will eventually decay and die. The image is not one of morbidity, but one of truth, much like historic images of saints contemplating the skull, in which the implicit concept was the cognizance of death, not the pursuit of it. Here, Woodman reaches a new level of thought: through evocation, she examines what it is to exist.

Woodman’s continued dialogue with the ideas of transformation and disappearance culminates in her later works that take on these issues in a historical context. While working at the MacDowell Colony in Peterborough, New Hampshire, Woodman created a collection of photographs that retell the story of Daphne in modern terms. One of these images depicts Woodman among nature, where she covers her arms in birch bark. Her arms sway, matching the motion of the trees in the background. The image of Woodman as a tree is evocative of the Tree of Life series of images created by noted feminist artist, Ana Mendieta, in 1976. In one of Mendieta’s images, the artist covers herself in mud to replicate the texture of the tree. She, like Woodman, performs a transformative act, associating herself with nature. Both Woodman and Mendieta explore woman’s relationship with nature through the lens of ancient myth. Whether there is influence from one to the other is difficult to determine, and perhaps, moot: both artists are engaging feminist renovation and interrogation of the stereotype of woman as nature.

In 1980, in New York, Woodman created a series of caryatid images. In one of the large-format photos, a blue diazotype, Woodman wears an elaborately structured and highly starched garment that mimics the aesthetic of both classical drapery and classical columniation. Reaching her arms up and bending her elbows, she obscures her face with her hands. Her forearms create a structural brace that supports the top of the picture frame. Here, Woodman has come full circle: once more playing with the idea of being and becoming a structural object, but now she is no longer absorbed by the domestic space. She has instead placed herself as an integral part of a classical structure and engaged in a classical allusion, which, unlike her Daphne reference, plays back into her earlier structural explorations in an intriguing way. This image represents the culmination of a series of self-depictions in which the viewer sees Woodman repeatedly, yet does not see her at all. Here, perhaps, is the finest example of the themes, which Woodman considered consistently. Woodman is indeed in the image, but the photo is actually of a column, not of a woman.

The fact that Woodman committed suicide at a young age naturally provokes a certain level of questioning about the reason she so often transforms and disappears in her work. Are these disappearances a precursor to her disappearance or a wish for transformation? While this can be posited, there is ample evidence that these themes have much currency in feminist art of the 1970s. Woodman explores the relationship of woman and domestic space that Bourgeois considered, and takes up the role of woman as nature imaged by Mendieta. The visual transformation and disappearances created by Woodman are not explorations of her own personal demons but of woman, literal and temporal, in space. Woodman can therefore be understood as a young artist interested in exploring the same concepts as her forebears and studying the changing relationship of woman in relation to her time.

- Francesca Woodman, Self-Portrait at Thirteen,1972

- Francesca Woodman, Caryatid, 1980

- Francesca Woodman, House #3, 1976

- Francesca Woodman, Space2, 1976.

- Francesca Woodman, untitled, 1979.

- Francesca Woodman, untitled (Daphne), 1980

- Aaron Siskind, Chicago, 1948, Photograph, 1948 © Aaron Siskind Foundation, courtesy of Bruce Silverstein Gallery, NY

[1] Phelan, Peggy. "Francesca Woodman’s Photography: Death and the Image One More Time." Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 27.4 (2002): 979-1004.

[2] The Woodmans. Dir. C. Scott Lewis. Perf. George and Betty Woodman. Lorber Films, 2011. DVD

[3] The Woodmans

[4] Krauss, Rosalind E. Bachelors. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 1999.

[5] Nochlin, Linda. Women, Art, and Power: And Other Essays. New York: Harper & Row, 1988.

[6] Zegher, M. Catherine De. Inside the Visible: An Elliptical Traverse of 20th Century Art In, Of, And From the Feminine. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 1996.

[7] Brigidi, Stephan. "Interview on Francesca Woodman." Personal interview. 11 July 2013

[8] Brigidi, Stephan. "Interview on Francesca Woodman." Personal interview. 11 July 2013