Paulina Perlwitz: Your work has always been oriented around the landscape as a motif or template. Can you talk about the evolution of that in your career as an artist?

May Babcock: Landscape at first was simply something to observe, absorb, and depict. It's also been a way to orient myself, by looking around and taking in my surrounding with thought and care. When I moved to Louisiana, this became more prominent. I think since many sites in south Louisiana are neglected, abandoned, and in a state of decay, the act of portraying my personal translation of places became more charged: psychologically, environmentally, and culturally. I realized that examining our contemporary landscapes, and specifically our non-idealized places, was my own way to act as a witness and documentarian. Landscape has been my jumping off point so far, and it's proving to be a complex motif that I've only just broken the surface of.

PP: How did you evolve from doing mostly 2-D work to sculptural pieces? Do you see there being a connection between the body in a space as directly relating to this evolution?

MB: At Louisiana State University, I had an 8 foot printmaking press pretty much to myself. Working a such a large scale lead me to print on cloth. These initial pieces showed me how impactful the consideration of the space around an artwork could be, in that case, scale and material. When I started making my own paper, I continued to display my flat work several feet away from the wall behind it, in order to give the paper as much life and movement as possible. This work was very much in the viewer's space. From there, it was an easy jump to collaborative installations and sculptural book forms.

PP: I remember in the past you talked about the metaphysical aspect of a figure within a landscape. Can you talk about that aspect of your work?

MB: Did I? That's a good word, metaphysical. I think if there is a figure, or a metaphysically to my work, it comes through a sense that these images are of specific sites. Or more accurately, there is sense of being at a place, rather than an exact photographic portrayal of what one might see. I generally draw sites that I find compelling, or that I feel strongly about. So that seems to be a basic notion of the metaphysical; that we are in a process of trying to comprehend our world. Part of my process does grapple with these philosophical concerns.

PP: How did being in different landscapes over the past few years affect your work?

MB: Artists in general are usually influenced by their surroundings in their life, and perhaps that's more evident and direct in my work than most. Rural Connecticut was just exactly that to me, a tree-filled, bucolic setting, at that time in my life. These landscapes for me were simpler, but still full of emotive qualities. Louisiana overall was a shock and huge change. There was definitely a period of adjustment, after which I started to seriously concentrate on sites showing evidence of decaying industry and agriculture. My work became darker, and many prints were reminiscent of discarded parchments or cavernous, hollow spaces. I've been in Providence now for a year and a half now, and I've only just started to readjust (again) and take in what Rhode Island is all about.

PP: Who are your biggest influences?

MB: I feel like I have a new influence each week! Here are a few: I'm taking another look at the variety of forms in Eva Hesse's installation work. I've been reading essays by Robert Smithson. The physically of Anselm Kiefer's painting and lead books are a definite influence. I'm inspired by my fellow papermaking artists, and the innovations in the medium that they are making.

PP: How do you see paper making as relating to man in his environment, if at all?

MB: Out of all the art-making processes I have worked with, I've found that papermaking is one of the most sustainable, and has the potential to be tied directly to location. Using recycled papers (trash), unwanted invasive plants, or even growing your own fiber to make your own paper is a way to be environmentally conscious in your studio practice. Also, if you're sourcing your own fibers, the resulting paper carries with it context, content, and characteristics specific to place.

PP: What were you main aims in your show at AS220?

MB: I wanted to take this opportunity show work that I've created very recently. This body of work is based on sites around Rhode Island and coastal New England, which is my way of beginning to engage with this semi-new location. It's also an exploration of the potential of paper making as a fine art process; there is no ink in this show, which is a first for me as a trained printmaking.

PP: I can see all those influences in your work. The physicality of Kiefer, the sense for touch and intuitive reverence for placement in Hesse's work. Robert Smithson's an interesting choice in relation to your work and makes me wonder if you ever think about making works that interact with the actual landscapes you've been making work about? Also Andy Goldsworthy I'm sure is someone people have brought up- in that vein of thinking. What do you think of Breaking down barriers between site specific and gallery work?

MB: I think my interest in Smithson is through his writings and interviews at the moment, not necessarily the placing work directly in a landscape. Though, I have done paper pulp casts at sites, but what you finally see is the cast displayed in a gallery setting. Right now, I'm interested in presenting materials and drawings removed from sites, and the translation of that through my studio process. I'm still in the middle exploring this vein, but a foray into site specific work in the future isn't an impossibility.

PP: So in your opinion the artist's environment has a direct influence upon the work; and certainly by extension the people he or she is interacting with in the making of the art. In the more immediate sense of environment- as in where one literally makes artwork, what is your ideal atmosphere? Do you have a studio? Is there a routine or schedule you follow on work days?

MB: When I refer to 'environment', it it meant in the broadest terms, from specific research to random interactions. And from all of that, when it comes down to making work, some things have more influence than others, whether from choice or intuition. I would love a big, open studio with plenty of natural light. Right now I've built the equipment I need and have it in my basement, a semi-private space that does the job. There is a lot of time at first that I have to put into preparing pulp, so a day or two is spent processing fiber (cutting, soaking, cooking, rinsing, beating), during which I read, plan, sketch, or do studio maintenance. When I have my pulp made, I have a week to two weeks to create what I need from the pulp before it goes bad (longer if I refrigerate it). You can get a sense of my rotating schedule tied to the the paper making process.

PP: Would you say you're more concerned with projection onto environment, as in the things we tell ourselves about our surroundings, or influx of environment, wherein we react to our surroundings via various bodily stimuli as if on automatic? I don't see this as an entirely polar model of thinking, and don't mean to reduce it to a dualistic viewpoint, but what do you think of those two different modes of experience in relation to your work?

MB: There is that duality there, but maybe it's more of a sliding scale more than one or the other. And I think we're also talking about objectivity versus subjectivity as well. Thinking about my process, it is a mix of both. I do a lot of reading to inform myself about the sites I visit, and writings ranging from economics to meta-trends in American society and attitudes and relationships toward nature, urban planning, history of agriculture…the list goes on. But when I make work, and when I draw and document, these things are at the back of my mind while I am absorbing as much as I can from a site. What comes out is most likely influenced by both.

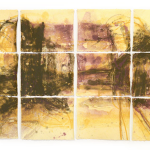

May Babcock, Seekonk River Mud Constructions, 16″ x 8″ each, Variable Installation, Handmade River Mud Paper, 2013. River mud was added to the vat of pulp and water before sheet formation.

May Babcock, Seekonk River Mud Constructions, 16″ x 8″ each, Variable Installation, Handmade River Mud Paper, 2013. River mud was added to the vat of pulp and water before sheet formation.PP: I remember the prints and paintings you did that were figurative and expressionistic in nature, and which had more of a quality of looking at the human form as subject matter whereas the subject of your work now seems to be focused entirely upon the mechanics of experience. The sculptures and hand made paper seem to be evoking something about a space or moment in time in a very different way than portraying a scene be it figurative or landscape oriented in nature. When did this shift occur and how you feel about utilizing "imagery" in the traditional sense now?

MB: The turning point was sometime during graduate school, and it was because of Louisiana landscapes. They were just so poignant, and had such a strong presence, atmosphere, and depth in so many ways. For me right now, using imagery in the traditional sense isn't as intriguing as this experiential way of conveying landscape. But what do I know? Things have a way of coming full circle sometimes.

PP: Where else would you like to travel to make work in response to?

MB: I've always been fascinated with places with minimal human presence. Places like the Zumwalt Prairie in Oregon, or the very deep south of Louisiana where the only access is with a boat or on roads on piers through the swamp. There's something about that vastness that is mesmerizing. I've never made work in response to places like that, but I would if the opportunity arose.

PP: "Contructions of Invasive Plants of Coastal New England" denotes an interest in botany and a proclivity for categorizing information based on color and texture. It reminded me somewhat of the Byron Kim flesh tone paintings. And seemed to be on a different trajectory than other works. Does that seem like something you might experiment more with? Like maybe categorizing tree bark or grass or rocks from different regions or just within the same area?

MB: It does have that sense of being a cabinet of curiosities, and I think it's because of my interest in the possibilities of using unwanted fibers from invasive plants in the area. I enjoy making paper from fibers that are plentiful and free (I used bagasse, or leftover sugarcane fiber in Louisiana), and around here, there's plenty of intense plants. It is my first foray into toying with the idea of presenting an area's natural or unnatural items. It's also a study of the natural characteristics of each fiber, so in that sense, this installation does have that element of objective study.

PP: Does the time based method of prep and plan and make hold any ritualistic value at this point? I'm so interested in people's work routines. It seems sometimes to be related to the kind of work they are making, if not directly in a paralleling sense.

MB: If there is anything ritualistic with my process, it's devoting the hours on end to simply working on turning something useless into something tangible: paper. Papermaking does have the restorative sense to it. Another thing that seems to happen is that such a long processing time gives me mental space and percolation time to decide what I might be making. And since there is a schedule of sorts to making paper by hand, it does dictate what needs to be done.

PP: The pulptypes have this intense gestalt to them- it's the feeling of taking in a scene from the visual cues we are given but not quite being able to put it together in any logical way. The effect is disorienting and requires of the artist a keen sense for pictorial depth perception. It's quite haunting and led me to wonder how you tune into those spatial shifts when you are in a space? Are these works made based off sketches? Memory? Photographs? And how do you choose what gets the focus?

MB: You use such great words! Gestalt! I might steal this for my artist statement. When I am at a site, I do sketches upon sketches of drawings of one view. Each sketch ranges from taking 5 seconds to 5 minutes. Then I usually move a few feet, turn a little, or stand up or sit down and go at it again. So I end up with a pile of sketches (sometime I do these on single sheets) that I have with me while I'm creating the pulptypes. When I make one, I work from a few sketches of the same view. Some of these sketches are quite spare, but stronger features and edges do repeat themselves through each group of sketches, and that is where I find focus and reference. I do take photographs too, maybe out of fear or paranoia I'm missing something, but later in the studio I never seem to look back at them. At least I have a running photographic record of places I've been, though.

PP: It seems like theres a lot of mirroring in the pulptypes- there's often the sense of symmetry as is seen when viewing sky and water, sky and land, or even like a double image someone might see when their vision is blurred. Where does this duality stem from in the pieces? Do you at all see it as being linked to the theme of interacting with one's landscape?

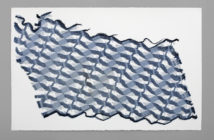

MB: The sense of duality stems from my process of drawing and redrawing, and playing with the amount of anchoring visual information to offer viewers. With these new pulp types, I think a sort of ambiguous duality comes forward even more because of the equipment I built to make them. I made a 2 foot square deckle box, which makes square pieces of paper and images. So, by necessity, I have to work in halves and overlap two pieces to create one whole.

PP: Could you describe the pulp process a little further for those of us who aren't familiar with paper making. What is a pulptype? How is a pulp painting created?

MB: I made up the term, pulptype, just a few months ago. I think it might help to briefly explain my hand paper making process as well. I start with natural fiber: from plants, cotton or linen rag cloth, or recycled papers. The fiber is cut up and soaked in water, and placed with more water in a machine called a Hollander beater. The beater mashes and cuts the fibers to form a pulp. Pulp painting fibers are typically beaten longer, and are a lot shorter than pulp you would used to make a normal, strong sheet of paper. The pulp is suspended in water, and drained through a screen, leaving a thin layer of interwoven fibers. This is then pressed to expel more water, and then the sheet is dried.

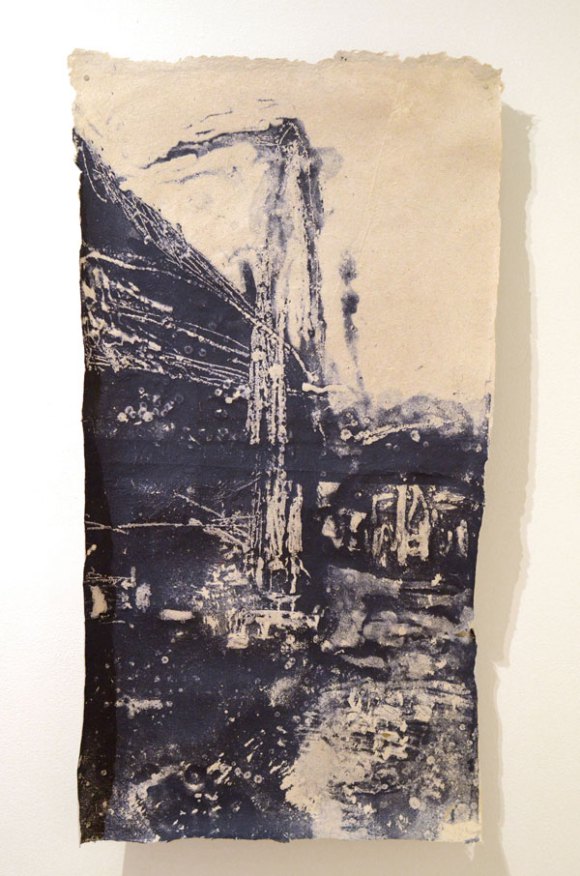

Pulp Painting is where you pigment paper pulp fibers, and pour, squeeze, paint, layer, or stencil the colored fibers to create imagery. I use aqueous dispersed pigments that attached themselves to the outside of each individual fiber, rather than seeping through like a dye. I usually used a blank base sheet that's still wet and freshly formed to paint with different pulps onto, before pressing and drying for a finished work that is made of entirely paper. This is how Mission Espada was made.

Pulptypes deserve the differentiation because it's more like a printmaking process: monotype. First, I form a base sheet and set it aside. Then, I form a very thin layer of finely beaten, pigmented pulp on a pellon (a type of smooth, slightly stiff fabric used in suits, also known as interfacing). Then I scrape, remove, and draw into that layer of colored pulp. Once I'm done with my drawing, I flip it over, face down, onto the wet base sheet I formed. I hand press with a sponge and then a brayer. The pellon is lifted away, leaving your pulptype.

PP: Do you listen to music while you work?

MB: All the time. When I'm doing something time-consuming repetitive, then's it M.I.A., David Byrne, or something with a beat that keeps me going. When I'm drawing/pulp painting, then it's a variety of classical (Bach cello suites, Chopin sonatas…) and softer music (Fleet Foxes to name one). Or I just put my iPod on shuffle!