The Icelandic singer Björk Guðmundsdóttir inaugurates the world tour for her new album Vulnicura with seven concerts in New York City, beginning in March 2015 in Carnegie Hall and ending in July at the Governors Ball Music Festival. She took the stage for her second concert in the majestically restored Kings Theatre in Brooklyn. Against a rapturous welcome, Björk began singing from her new album accompanied by the string orchestra Alarm Will Sound, the percussionist Manu Delago, and the electronic musician Arca. She wore a diaphanous white dress that concealed the contours of her body and an enveloping headpiece composed of yellow-tipped quills that formed a halo around her. Throughout the first half of the concert, the dress’ motorized chest piece gradually opened so that before intermission, the artist’s core was opened to the audience as if a pair of wings had sprouted from her heart’s center. The music progressed lugubriously at first, marked out by the primordial and steady heartbeat of a drum. The scene recalled choruses of angels on medieval altarpieces, rudimentary yet sublime.

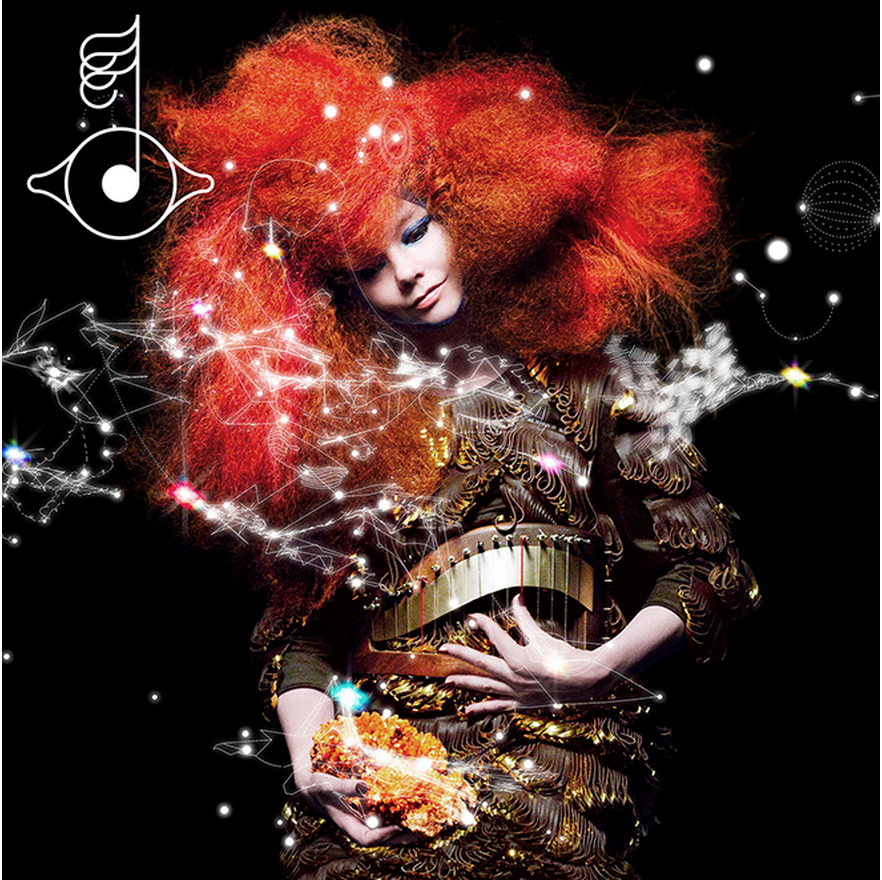

Björk, Biophilia, 2011

Credit: By M/M (Paris) Photographed by Inez van Lamsweerde & Vinoodh Matadin. Image courtesy of Wellhart Ltd & One Little Indian

Curator Klaus Biesenbach at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA) has long wished to mount an exhibition devoted to Björk’s multi-media artistry and finally was able to do so concurrently with the New York concert series. The exhibition at MoMA consists of three main components, all housed in a custom-built temporary structure in the midtown museum’s atrium. Visitors file into a dark chamber to experience Black Lake, a music-video installation commissioned by the MoMA for a single from Björk’s new album. Surrounded by dozens of speakers and two projections on opposite walls, visitors in the center of the installation look back and forth nervously as if they might miss something each time they turn around. The video, directed by Andrew Thomas Huang, begins in a Lascaux-like setting, a dark Icelandic grotto. Eventually emerging from her cave, the artist beats a jagged rock until it breaks open, spewing molten blue lava. After this experience, visitors are shepherded to a small cinema with cushioned lounge seating where thirty-two of Björk’s music videos are played on a continuous loop, covering the arc and maturation of the artist from the early 1990s to the present.

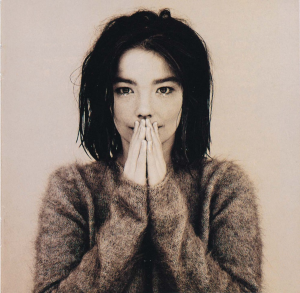

Björk, Debut, 1993.

Credit: Photography by Jean Baptiste Mondino. Image courtesy of Wellhart Ltd & One Little Indian

Above Black Lake and the Björk cinema, visitors cue to enter Songlines, a series of rooms based on the artist’s eight albums. An audio guide monitors the wearer’s position within the exhibition and accordingly moves through segments of a pre-recorded narrative. Björk worked with the Icelandic poet Sjón on the story line, which is narrated by Margrét Vilhjámsdóttir’s fairy-tale voice. Visitors are invited to follow the episodes of "a girl who lived alone in a lava filed in a forest by the ocean" through a set of adventures, loosely corresponding to the characters developed for each of Björk’s albums. The narrative explores a tension between city and countryside, mainland and island, love and loneliness. As the story culminates in Vulnicura, an album full of references to Björk’s painful breakup with the artist Matthew Barney, it is deceptively easy to understand the entire story as one of love and heartbreak. Elsewhere, however, Björk has spoken about her proclivity for solitude and camping alone in the forest. For her, human company can cause loneliness just as much as nature can offer company. Love, in Vulnicura, as in Songlines and Björk’s larger oeuvre, must be understood as encompassing far more than romantic love between humans.

In full, Songlines takes roughly forty minutes, though lacking patience, many visitors move through it faster than they did the line to get in. The temporary exhibition pavilion is black and dimly lit. Conspicuously absent are the sight lines that generally denote visual continuity between the various galleries of an exhibition. The curatorial hope was presumably that visitors would be guided through these spaces by the aural rather than the visual. As a result, some of the most interesting pieces in the exhibition go unnoticed. A guard commented that few visitors stop to watch the enormous projection in the atrium of the black and white video for Big Time Sensuality (1993), shot in the streets of New York City. The lobby is also dotted with musical instruments developed expressly for Björk, including the Tesla Coil that creates a lightning show when played, harps activated by the earth’s gravitational pull, and a hybrid celeste-gamelan, all of which were operated from iPads during the Biophilia concerts (2011-2013). These significant contributions to the musical instrument family resulted in an iPad app, the first ever acquired by MoMA. These musical-digital Etch A Sketches are available for visitors to handle by the architecture and design galleries on the third floor. It is unlikely, however, that MoMA visitors trying to take in the permanent collection and the Björk exhibition in a single afternoon have the time or patience to track down these additional Easter eggs.

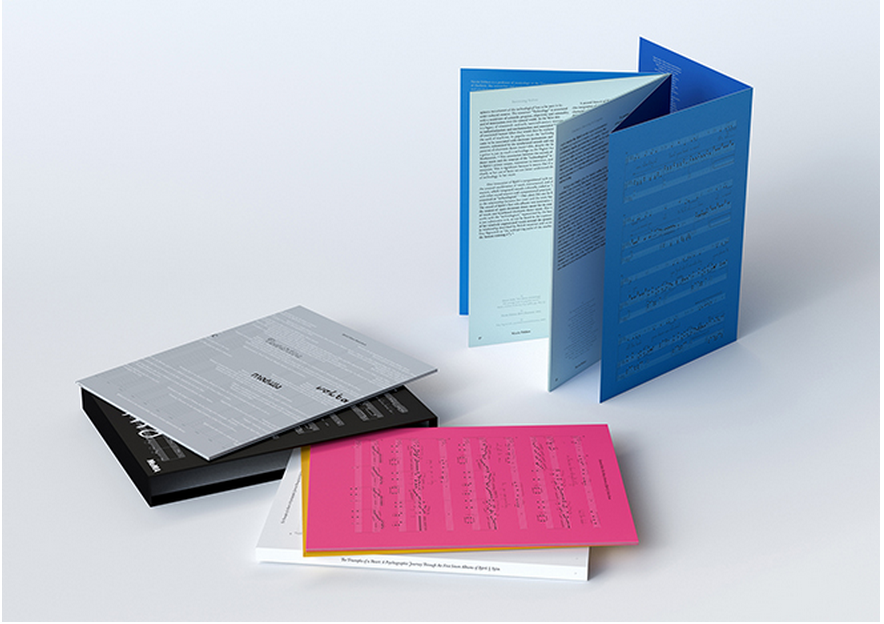

The Björk exhibition catalogue consists of five parts in a box set, each bound to simulate elements of musical scores and LP records. It is a beautiful object to behold, though after accessing much of the artist’s output through touch-screens and apps, flipping the printed pages feels anachronistic. Contributions by the curator Klaus Biesenbach, music critic Alex Ross, musicologist Nicola Dibben, and the philosopher Timothy Morton are provocative and informative but as a whole do not come together as a serious work of scholarship. With the exception of Ross, the authors largely footnote themselves and base their observations on conversations with the artist or highly personal experiences with her music rather than archival and historical materials.

Art critics have lambasted the exhibition. It certainly could have been done differently but I was actually relieved that the museum failed to pioneer a new paradigm of visual-musical exhibition thereby leaving that task to more nimble institutions. Critics frustrated by the ersatz effect of viewing Björk’s costumes, notebooks, and concert paraphernalia might be equally disappointed to know that some of the works in the museum’s permanent galleries are also "fake" exhibition copies. Part of the critics’ disillusionment stems from looking too hard at the walls and rejecting the conceptual, multi-sensory experience itself as the work on offer. That requires sitting down, spending at least ten minutes in each of the Songlines chambers, closing one’s eyes, and losing oneself in the audio guide’s narrative rather than giving up on its lack of linearity. Björk’s modus operandi, in which the relationships between objects are more important than the objects themselves, demands more vulnerability and introspection than most critics were able to summon.

The other part of this disillusionment with the exhibition stems from the fact that while many of the pieces on view are works of art in their own right, it is difficult to separate them mentally from the music they were originally called upon to serve. Unlike the museum’s 2010 exhibition Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present, the Björk exhibition is explicitly not a performance, and the costumes and ephemera are not called upon to serve an ancillary role to Björk as a performer. They are autonomous aesthetic statements involving hours of painstaking labor, as with the matrimonial dress of pearls and body piercings Alexander McQueen designed for Pagan Poetry (2001). Chris Cunningham’s robots for the music video All is Full of Love (1997) are at least as impressive as those by contemporary artists such as Jordan Wolfson or Andro Wekua. Nick Knight’s "Homogenic" animation is just as entrancing and meticulously composed as the light boxes of Jeff Wall and Yael Bartana or Thomas Wilfred’s Lumia. Such works in the Björk exhibition could easily stand alone in a gallery, as some have in the past. The only difference between them and the works in the museum’s collection galleries is that Pablo Picasso’s paintings and Donald Judd’s sculptures were rarely intended to support another medium such as music, and therefore critics have an easier time understanding how they function visually. One of the keys to appreciating the Björk exhibition is accepting that academy-trained, gallery-represented artists with careers independent of the singer made many of the works on view.

Björk was implicated in the history of art long before her MoMA retrospective in a number of ways that surprisingly are nowhere evident in the exhibition. There is no material relating to Björk’s contribution to the 2005 Icelandic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale and no wall labels indicating her collaboration with artists such as Juergen Teller. Björk’s animated musical scores for Biophilia (2011) are projected onto the stage wall behind her, setting abstract geometric shapes in motion according to the rhythm of her voice. These works bear an uncanny resemblance to the pioneering abstract films of Walter Ruttmann or Hans Richter, who worked with the composer Paul Hindemith on a machine that synchronized a rolling film score with an accompanying projection. This was an early version of precisely the intermedial innovation Björk brings to the stage.

In the catalogue, the curator inserts Björk into a lineage of performance art that includes Marina Abramović and Pipilotti Rist, two of the artists he has championed with exhibitions in the very same atrium at the MoMA. But the German artist Joseph Beuys would be an equally possible starting point for that conversation. Beuys surprised audiences in his 1969 performance Titus Andronicus/Iphiginie with heavy breathing extremely similar to the deep inhalations and exhalations that distinguish Björk’s vocal style. Like Beuys, Björk uses her body to gesture to the anthropomorphic qualities of non-human entities, felt and wax in Beuys’ work, constellations and robots in Björk’s. As Beuys used the melting and hardening of lard to analogize the malleability of human nature, Björk’s Black Lake thematizes the process of transformation between solid and liquid in the natural landscape as in the human body. The parallel is most apt in terms of the artists’ self-mythologizing, Beuys’ narrative of being shot down over the Crimea and saved by nomadic Tatars and Björk’s of a girl who ventures from nature to the urban environment, eventually returning to the forest from which she came. MoMA, supposed custodian of modern art oddly does not touch upon Björk’s unmistakable relationship to the history of that art.

Björk’s song Bachelorette (1997) is in many ways a road map for the MoMA exhibition. The lyrics, written by the same Sjón who helped develop Songlines, follow a young woman whose autobiography writes itself as she moves from the country to the city, falls in love with a publisher, and turns her story into a best selling book and musical production. At one point, the music video pans from the city streets in which the bachelorette exists alongside her fans, to the theater stage, where the bachelorette performs her story for an audience. The scenario is then doubled and tripled as the camera zooms out to show a theater within a theater within a theater. The kaleidoscoping of the protagonist’s story from personal to estranged in the hyper-mediated form of musical theater, is exactly what one feels in the MoMA’s exhibition. But the museum visitors are not the theater audience watching the staged spectacle; they are rather the actors milling about on stage interacting with props in a contingent reality. At the end of the music video, the bachelorette realizes the city is no place for her and winds up back in the forest where she began. The exhibition takes its viewers on a similar journey, one that covers much ground but leads nowhere.