Two of today’s more compelling shows consider work that was made or displayed for the first time at around the same point. Boston’s ICA of course has This Will Have Been: Art, Love, & Politics in the 1980s, which attempts to "re-examine this tumultuous decade," and the New Museum has NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash, and No Star, which is "a time capsule, an experiment in collective memory." There are compelling similarities to these shows and I believe that each informs the other. 1993 was an interesting moment, but the changes inherent in the artworks from that year did not come fully formed from the head of Zeus: they were much more grounded than they seem. To find the reasons behind the work, I think you need to look to the 1980s.

The 1980s, of course, are a decade and 1993 is a single year, so one of these exhibitions is going to have a tighter focus and a narrower purview than the other.

Both contain a couple of the same artists (Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Nan Goldin, Greg Bordowitz) but their themes dovetail better than the artists. The cardinal example is art’s reaction to AIDS, which has its achingly sad foundation in the 80s but has a more mature, and yet still piercingly intense reaction in 1993.

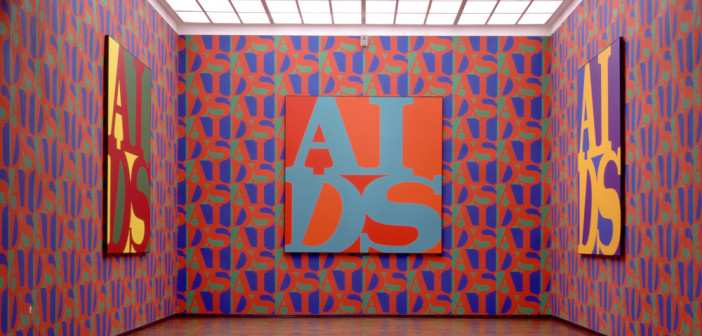

Bordowitz’s video Fast Trip, Long Drop (1993) is in both shows and, after seeing NYC 1993, I now wonder why it was included in This Will Have Been. The other works at the ICA about AIDS are best described as agitprop about the political blind spot that the Reagan/Bush administration(s) chose to maintain about AIDS—Donald Moffett asks you to Call the White House, General Idea made wallpaper in fun colors that riffed on Robert Indiana’s Love Statue. HIV in the 1980s seems an inchoate and tense abstraction that can be seen through the lens of the propaganda surrounding it. While in 1993, Borowitz was not afraid to show the personal side of HIV by presenting an HIV support group’s conversation. To oversimplify how NYC 1993 changed how I see the inclusion of Bordowitz’s video at the ICA: You see real people in 1993, you see stock photography in the 80s. It may increase the story of how artists reacted to HIV, but it seems out of place in the story of the '80s, partially because it isn’t from the '80s.

The agitprop of the '80s attempted to set the tone for our civic discourse, using the power of graphics to spark the public’s awareness of the disease. The propaganda seems unified and coherent compared to the range of political alternatives in 1993. Genuine anger about how we as a society reacted to HIV is evident in both shows. There were real and specific questions about the scientific community’s responses to HIV and a discouraging lack of clarity about if this was a disease we could eradicate or if it was a death sentence. Nan Goldin: "At that stage, we still didn’t know very much. There was a lot of ignorance. We were very obsessed with what caused it: There were all kinds of rumors, everything from amyl nitrate to bacon."1 As time passed, and the unknown became known, GRID became ARC, which then become AIDS in 1986. In 1987 Reagan had finally mentioned HIV/AIDS after more than 20,000 people had already died. His silence and indifference doubtlessly did equal death for some.

Goldin’s work transitioned from the past tense—a complicated documentation of her circle of friends in her Ballad of Sexual Dependency—to the present tense—a specific and politically astute consideration of her specific friends' lives in Gilles Dusein and Gotscho, 1992-1993. Her image-making changed from an extended archive to a powerfully empathetic portrait format, which was imbued with real political outreach. Seeing the casual and wanton life that people were living in The Ballad of Sexual Dependence seems like a quaintly ignorant and impossibly distant era from the careful and self-conscious way that HIV+ people were trying to live their lives in 1993.

Another theme that you can find in both shows is the "palimpsest of national identity"2 or the intersectionality of political modalities: race, sexual orientation, gender, and cultural memory. Where the Black Audio Collective’s (BAFC) Handsworth Songs is very specifically based on documents, and Issac Julien’s Searching for Langston is based on a sensuously affectionate impressions, Byron Kim’s work on skin tones from 1993 has made the question of race and culture both more and less specific. A person’s skin tone is unique and it’s unrepeatable, but it does not ascribe a political reality to the person being observed like the other two videos do.

David Hammons, In the Hood, Athletic sweatshirt hood with wire, 1993.Courtesy Tilton Gallery, New York

David Hammons, In the Hood, Athletic sweatshirt hood with wire, 1993.Courtesy Tilton Gallery, New York

The BAFC’s hour long video creating an oral history for Afro-Caribbean residents of Handsworth (a section of Birmingham) is an attempt to mainstream the experience of the 1985 riots. Rather than creating a fixed, first-person narrative by only interviewing participants, the BAFC instead created an archive of found material from a diverse range of sources and create a collage from that archive. This film comes only a few years after BAFC’s experiments with found images and text that were shown in galleries via a slide projector.

The Handsworth Songs reminds me of Glen Ligon’s untitled 1988 painting referencing the 1968 Memphis protest signs that read "I Am A Man." Both are attempting to secure a voice for the people involved and both portend a wider social struggle. In both cases, what seems like an obvious statement becomes an indistinct gesture once it is translated into an artistic format. Is Ligon declaring his manhood, is he using a readymade historical artifact to assert a political stance, or a bit of both? Is BAFC associating with the riots for historical reasons, or is it more intimate than that?

Both shows attempt to show the interactions of these differing political boundaries. There is not such a clean line between sexual orientation, gender, race, and having a political voice. One cannot assume that an artist is just talking about one of those circumstances any longer.

Ligon’s Red Portfolio (1993) functions similarly to Untitled (I Am A Man) as it appropriates the language used to describe images from Robert Mapplethorpe’s X Portfolio. Images from Maplethorpe’s X (1978), Y (1979), and Z (1981) portfolios became glaring political targets in 1989 when Robert Maplethorpe: The Perfect Moment attempted to tour to the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington DC. Mapplethorpe’s work was used as a political weapon during the early '90s by conservatives who were trying to defund the NEA and Ligon’s portfolio presents these images through the words that were used to describe the photographs in Pat Robertson’s list of "Photographs too vulgar to print."3

Ligon’s photographs are made up of Robertson’s words, simply presented in white against a black background. The words are small enough that they come into focus as you get closer to them. The power is in the image’s absence.

This bit of political theater from the Christian Coalition resonated in 1993 because it seemed like the NEA was going to have to either shut down completely or stop funding individual artists. The NEA did the latter in 1994, a year after Ligon created this portfolio.

The objects we make are, consciously or not, indebted to our histories. The New Museum attempts to set the mood through general facts about 1993 via an assemblage of televisions on the fifth floor, but I think looking at the objects and themes found in Helen Molesworth’s This Will Have Been may be a better way to understand what instigated 1993’s developments. Maybe that's my specialist bias—that the history of art is more informative than flipping through the type of information you'd find in old Newsweek magazines—but for these works, which are very specific, their obscurity is not in how they relate to our general culture but how they are connected to art history. In the other direction, the advancements found in the 1980s can be seen as a substructure, a pre-history that is dead and buried by 1993, or we can see how the artists from the '80s were validated or snubbed by later work; as if they were still alive and able to talk back. Most of them were, or even still are.

Is everything even and levelheaded in these two shows? Not by any stretch. There are more conversations that should be had because of these shows (Is contemporary art history a slave to the market for one) but their attempts to index the art objects from these eras gives us a great excuse to read into our recent past and start filtering the work and wondering if work that didn't "make it" should have been included.

- Daniel Joseph Martinez, Museum Tags: Second Movement (Overture) or Overture con Claque — Overture with Hired Audience Members 1993 Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, Metal and enamel on paint, 1993. Courtesy the artist and Simon Preston, New York

- David Hammons, In the Hood, Athletic sweatshirt hood with wire, 1993. Courtesy Tilton Gallery, New York

- Installation shot of In Honor of Allen R. Schindler by Marlene McCarty and Donald Moffett for Bureau, NY and Wedding Series: Portrait of Robert Nickas and Alix Lambert by Alix Lambert. Courtesy New Museum, New York. Photo: Benoit Pailley

- General Idea, AIDS Wallpaper, Screen print on wallpaper, 1989 Courtesy of AA Bronson

This Will Have Been: Art, Love, & Politics in the 1980’s is on view at the ICA Boston through March 3, 2013.

NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash, and No Star is on view at the New Museum through May 26, 2013.

[1] Nan Goldin, at the website 20 YEARS: AIDS & PHOTOGRAPHY http://digitaljournalist.org/issue0106/voices_goldin.htm

[2] The Ghosts of Songs: The Film Art of the Black Audio Film Collective, 1982-1998, Kodwo Eshun and Anjalika Sagar, Liverpool University Press, 2007. Pg.137

[3] Outlaw Representation: Censorship & Homosexuality in Twentieth-Century American Art, Richard Meyer, Beacon Press 2004. Pg 3-5