Some of my fondest memories during my college years can be traced back to my art and architectural history courses, sitting in a dark lecture hall absorbing the sights and sounds that emerged from the slide projector. The slide projector, as we know it today, dates to 1935 when Leopold Mannes and Leo Godowsky invented a process that would later be patented as Kodachrome. Considered now an obsolete technology only used by stubborn college professors who refuse to teach art history using digitized images, the slide projector revolutionized the way we looked at pictures. The act of looking became a communal experience as people gathered around a projector to relive—through much bigger, brighter, and color-saturated photos—the thrill and excitement (or lack thereof) of family vacations. Currently at the Institute of Contemporary Art, confined to a paltry side gallery is Luther Price’s installation of 400 handmade slides projected using five projectors, that's roughly 240 slides and 3 projectorsless than what the exhibition's catalogue states.

Of all the finalists in this year’s Foster Prize, the Revere-based filmmaker is perhaps the best known. Featured in the 2012 Whitney Museum Biennial and most recently in Second Nature: Abstract Photography Then and Now at the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum in Lincoln, MA, Price has been making films since the late eighties and has had his films screened at prestigious venues and events such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the New York Film Festival’s Views From the Avant Garde program, among others. Trained as a sculptor at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design where he is currently professor, Luther Price has made more than 200 films, most of which only exist as single-copy originals.

As a medium adopted by the Conceptual artists of the 1960s whose definitions of art radically expanded to include technologies then considered too familiar, accessible and low brow, slides remained until the arrival of digital photography, the means for reproducing and illustrating one’s work as an artist1. For many spectators of a younger generation who have seen or will see Luther Price’s installation at the ICA, the sight of a slide projector in a contemporary art museum may come across as a bit of an anachronism. For those of us who grew up with the slide projector, memories of a by-gone era will emerge as one tries to make sense of the lush imagery that flash before our eyes.

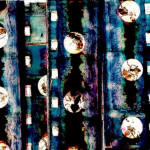

#9 A Study in Decay, 2012 is projected in a row with each slide shown at a time interval of five or six seconds of each other. The installation recalls a continuous film reel, blurring the lines between photography and film. To make his slides, Luther Price paints, processes, punctures, scratches, stains, burns, collects and presses dust and other particles, including insects into the film, resulting in an outburst of colors, patterns and textures so intense, that they beg to be touched, licked and savored. But of course, these only beg to be touched, licked and savored until one reads the interview in the exhibition's catalogue with curator Helen Molesworth and Luther Price. In it, Molesworth states that Price's work is about "decay or the biological problem of death." Price responds by saying that he has been studying decay for the past few years and that "[t]he slides become sort of a specimen." Rather than being about decay or the biological problem of death as curator Helen Molesworth thinks Price's work is about, Luther Price's slides could almost be seen as tools one could use for testing, examining, or studying insects, hairs, or tiny dust particles invisible to the naked eye. They're more about the beauty of life and all the tiny organisms and fragments that make up anything and everything in and around us, than they are about decay or death.

Price's slides recall the work Aldo Tambellini made in the 1960s also by scratching and painting onto the surface of the film. While Tambellini’s films are mostly all black (and they are films, not slides), Price’s slides are profusely colored and richly layered with found footage or discarded film fragments. The slides are evocative, producing a visceral effect that is felt in the "gut." "Many times I will get really involved in color as one of my main aesthetic issues so I’ll say ‘hmm there’s a lot of green here’ and start collecting different textures of green. So color is many times a major issue for me, a path towards finding something within the structure of the film. Of course, the content becomes a major issue too," said Luther Price in conversation with filmmaker Tara Nelson for Big Red & Shiny’sOctober 2012 Journal.

When Luther Price said his slides "become sort of a specimen," membranes, ribosome, chloroplasts, fungi growing in petri dishes and color-enhanced micrographs of pollen immediately came to mind. The slides become a typology of "elements" or "things" that belong in a category all of their own.

Luther Price’s installation revisits that communal experience slide projectors once created, with museum spectators immersing themselves in the act of guessing what some of the images depicted in the slides may appear to be. Their chit-chatter, along with the sound a slide projector makes, are the only soundtrack to this lush, highly obsessive and fetishistic film-like installation. In the same interview with Helen Molesworth published in the exhibition's catalogue, Price states that he started setting up multiple projectors and filling the space with images and "working with the space and the idea that when it's all over and the lights go up, everything disappears." Rather than play with spatial relationships of the ICA's boxy interior or inundate an entire gallery with color, the installation feels overcrowded (then again, so does Mark Cooper's and Katarina Burin's installations), confined to a meager gallery space that oppresses the spectator and also diminishes the work itself. If the curatorial intention was to make Luther Price's work to be seen in an intimate space, then it is way too intimate for even the most intimate of spectators. It's a shame, because from what I have read about his work in the Whitney Biennial, curators Elisabeth Sussman and Jay Sanders got it right from the start.

_____________

Every two years the ICA holds the James and Audrey Foster Prize by creating a short list of Boston artists of "exceptional promise" and establishing a panel of professionals to assess those artists. All four of the short-listed artists exhibit at the ICA, and one is announced as the James and Audrey Foster Prize winner.

This year’s short list is Sarah Bapst, Katarina Burin, Mark Cooper, and Luther Price.

This year’s jury is Mark Dion, artist; Paul Ha, director of MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge, MA; and Ali Subotnick, curator at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA.

This week we will be running reviews for all the artists on display. They will be in alphabetical order.

We here at Big Red & Shiny congratulate Katarina Burin for winning this year’s James and Audrey Foster Prize.

- Luther Price, #9 A Study in Decay, 2012, 640 handmade glass slides, 8 projectors, slides: 2 x 2 inches, projected images. Dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist. Photo: John Kennard.

- Price with #9 A Study in Decay at the Institute of Contemporary Art. Photo: John Kennard.

- Installation of #9 A Study in Decay at the Institute of Contemporary Art. Photo: John Kennard.

- #9 ‘oxcidation blue’, 2012. Image courtesy of the artist.

[1] Darsie Alexander et al., SlideShow: Projected Images in Contemporary Art (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005), 4.