By CARL CHIARENZA

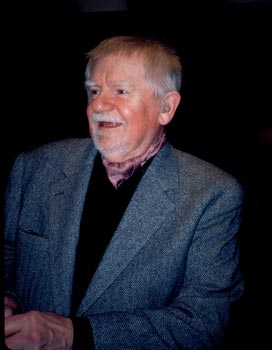

Carl Siembab

January 5, 1926 - February 27, 2007

Half a century ago Carl Siembab began exhibiting photographs in his Newbury Street gallery in Boston. It was the beginning of a pioneering effort that developed into a force -- a force in the flowering of photography in the world of art. Before devoting his gallery exclusively to photography, he exhibited photographs along with paintings, sculpture, and prints. He barely made a living. In 1959 he put up major one-person shows by Aaron Siskind and Berenice Abbott. That was the beginning of a chapter in the history of photography. His deep understanding of a body of work was evident in his regularly applauded arrangements of the work on the gallery walls.

By the early 1980s, he was in serious debt; ironically, his efforts had been eclipsed by the rise of interest in the medium elsewhere, primarily in New York City.

Siembab was a large, quiet, gentle man whose eyes were penetrating. He was an artist who understood art and artists in an uncanny way. He moved slowly and silently, until he felt a rapport between visitor and art. Then he would show his passion in animation and word. That passion for art is what sustained him and what permeated his exhibitions, his discussions -- private ones as well as those that happened with increasingly large groups of artists, students, and art lovers that work-shopped and brainstormed long into the evening at the gallery.

In the post-World War II world of photography (after the loss of Alfred Stieglitz, who is seen by some as Siembab's role model), no one did more to bring serious public respect to the art and artists of photography. He did it, essentially alone, when there was little interest at large, and no visible hope of making a reasonable living from his work. That never restrained him. He was blindly (naively?) committed to the project. He educated a growing community of artists, curators, collectors and new gallery operators. He set standards for himself and others. He was a risk-taker while being a mentor. And when what he started blossomed into a vast enterprise, Carl celebrated the rewards for artists while decrying the accompanying commercialization.

Lee Lockwood wrote, in 1981, that Siembab was "an incalculable influence on the development of public acceptance of photography as an art form." That accomplishment, paradoxically and unfortunately, was to have a nearly catastrophic effect on Siembab's future. He had very little ability in business -- a conflict (perhaps even a contradiction) of his life that he could never resolve. That fact has caused him to be largely forgotten. And it began the decay of his life as he was forced to leave a dream that failed to provide him with a reasonable living.

As Robert Taylor wrote in the Boston Globe in 1963, the Carl Siembab Gallery graced the artistic scene with "honesty and integrity." He studied, seriously studied, the work of his artists and the work of their historical predecessors. He could teach a rich history of art; he could teach a passionately critical approach to the aesthetic appraisal of artworks. Carl's gallery was unique, and the person was unique. I cannot imagine either happening again on this earth. The respect he earned from artists is rarely seen in today's art world.

Another disconcerting irony is evident when one recalls a statement Siembab made in an interview in 1971 by Robert Brown for the Archives of American Art: "I have a ... fanatical belief in the integrity of photography as an artistic medium. I also strongly believe that it will be the most significant medium in the coming generation.... I think most of our artistic experiences will come through some photographic means." (Quoted by Kim Sichel in Photography in Boston, 1953-1985, MIT Press, 2000)

As a friend of his artists, Carl was for life, committed, concerned, supportive, always interested in the whole person. Only financial matters strained friendship. When art was not the focus, pleasure was. And pleasure was as passionate an endeavor as was art. Siembab had a rich, broad, bawdy sense of humor, which was shared, within the ever-growing circle of his friends. He loved nature -- whether in the woods surrounding his log cabin or in the lovingly nourished plants he housed in the gallery and at home. In a way his closeness to nature suggests his natural talent as a fine craftsman, an artist, and a connoisseur. It also underlines his concern for his artists, his friends. His support of them was not unlike the care he gave his plants. Those who worked alongside him in the "vineyard" that was his gallery flourished under his care because of his critical and loving attention.

Image by Charles Giuliano.